Surgery to anatomically and securely repair the torn anterior glenoid labrum and capsule without arthroscopy can lessen pain and improve function for active individuals.

Download this article in pdf format.

In this Article:

Overview

The normal shoulder is a marvel of mobility and stability. It provides more motion than any other joint in the human body. Throughout the wide range of shoulder activities, the humeral head (ball of the shoulder joint) remains precisely centered in the glenoid (the socket of the joint). One of the main stabilizing mechanisms is concavity compression. Concavity compression is the mechanism in which the head of the humerus is held into the glenoid concavity by the action of the rotator cuff (much like a golf ball is held into the concavity of a golf tee).

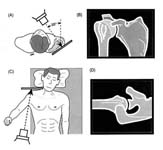

Figure 1 shows the humeral head, the glenoid, and one of the muscles of the rotator cuff. The concavity of the shoulder socket is deepened by a fibrous ring known as the glenoid labrum (See clip 1, glenoid labrum). The glenoid labrum greatly increases the stability of the shoulder (See clips 2 and 3, suction cup and concavity compression). Another stabilizing mechanism is ligament restraint, in which the motion of the shoulder is kept within the proper range by ligaments that span the joint (See clip 4, glenhumoral capsule).

The glenoid labrum and the ligaments can be torn when the arm is forced backwards, allowing the humeral head to dislocate from the glenoid. If the labrum and the ligaments do not heal, the shoulder may continue to be unstable, allowing the ball to slip from the center of the glenoid even with minimal force.

When recurrent shoulder dislocations or feeling of instability interfere with the comfort and security of the shoulder, a repair of the ligaments and labrum by an experienced shoulder surgeon can usually restore the stability of the joint.

The patient with an unstable shoulder requires a thorough history and physical examination along with proper x-rays.

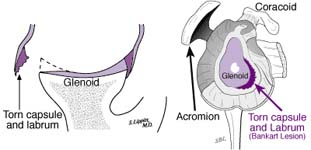

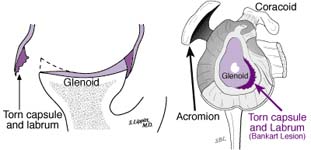

The most common form of ligament injury is the Bankart lesion, in which the ligaments are torn from the front of the socket. A solid surgical repair requires that the torn tissue be sewn back to the rim of the socket. Failure to secure this lesion solidly can result in failure of the repair.

If the glenoid bone is deficient, the shoulder may benefit from a surgery to restore the lost bony anatomy.

10 surgery questions for your surgeon before having surgery

Bankart Repair Image Gallery

Bankart Repair Movie Clips

Embedded below are 12 short movie clips. The clips below are referenced throughout this article. Clips embedded below include examples of shoulder antaomy and demonstrations of selected steps of the Bankart repair procedure.

- Clip 1 - Glenoid Labrum

- Clip 2 - Suction Cup

- Clip 3 - Concavity Compression

- Clip 4 - Glenohumeral Capsule

- Clip 5 - Diagonal Path

- Clip 6 - Subscapularis Incision

- Clip 7 - Bankart Procedure

- Clip 8 - Rough Lip

- Clip 9 - Glenoid Holes

- Clip 10 - Glenoid Sutture

- Clip 11 - Labrum Suture

- Clip 12 - Subscapularis Repair

Symptoms

Characteristics of shoulder dislocations

Instability is a common cause of shoulder injury; shoulder function can usually be improved by a surgical repair. Individuals with shoulder instability usually notice that the shoulder feels unsteady or the ball may actually slip out of the joint in certain positions, such as when the arm is out to the side or across the body. People with anterior (frontward) instability of the shoulder have difficulty throwing because this action depends on normal ligaments across the front of the joint as shown in the Figure 10, below.

Types of shoulder instability

The most common type of shoulder instability is traumatic anterior instability. In this type of instability, the ligaments and the labrum at the lower front part of the shoulder are torn by an injury that occurred when the arm was out to the side.

Figure 11, below, shows, in cross section, the capsule and labrum torn from the edge of the glenoid socket. Note that the damaged socket resembles a golf tee with one of its edges broken away so that the golf ball will tend to roll off of it. The image in the right side of Figure 11 shows the same injury looking at the socket with the ball removed. The gap between the glenoid and the torn capsule and labrum is where the ball dislocates. The tear of the labrum and capsule from the glenoid is called a "Bankart Lesion".

Common causes of this injury include a skiing fall with the arm out to the side, a clothesline tackle, or a blocked spike in volleyball. The shoulder may not pop back in the joint, but instead, often needs to be put back in place by experienced assistance such as in an emergency room. The dislocated shoulder is given a chance to heal; then the patient is started on a rehabilitation program.

Not infrequently, the labrum and the ligaments do not heal completely and the shoulder continues to feel unsteady (for example, when the arm is moved out to the side and backward). These injuries seriously compromise the stability of the shoulder. An unhealed Bankart Lesion can result in recurrent anterior shoulder instability. When multiple dislocations have occurred the chances of healing without surgery become small.

A similar type of injury can occur to the back of the joint (traumatic posterior shoulder instability), but it is much less common. Traumatic posterior instability arises from mechanisms such as a fall on the outstretched hand.

There is another type of instability which arises without an injury--atraumatic instability. In this condition, the shoulder loses its normal ability to center the ball in the glenoid socket. Not infrequently, atraumatic instability may allow the shoulder to slip in different directions (multidirectional instability). In this condition there is usually nothing torn, but rather, the stabilizing structures of the shoulder decompensate.

Diagnosis

Shoulder instability must be distinguished from other causes of shoulder dysfunction such as arthritis, rotator cuff tear, and snapping scapula. Arthritis usually results in shoulder stiffness and pain; X-rays show the loss of the joint space. Rotator cuff tear results in shoulder weakness. In snapping scapula, the shoulder pops when the shoulder blade is moved on the chest wall.

Shoulder dislocations are among the most common conditions of the shoulder. They are more likely to be found in people from 15 to 35 years of age. Individuals over the age of 40 who dislocate their shoulders are likely to also have a tear of the rotator cuff. Those who have instability of one shoulder are somewhat more likely to have instability of the opposite shoulder. People with loose joints are more likely to have atraumatic instability.

The experienced shoulder surgeon can make a diagnosis of shoulder instability from the patient's history and from the physical examination. In traumatic instability, X-rays may show damage to the humeral head (ball of the shoulder) or the glenoid (socket). Complex tests such as MRI or arthroscopy are rarely necessary to make the diagnosis.

It is essential that the surgeon establish the diagnosis of shoulder instability before surgical treatment is considered.

Treatment

Medications

Medications cannot help the healing of a torn labrum or ligament. Mild pain-relieving medications can be used to make shoulders with instability more comfortable.

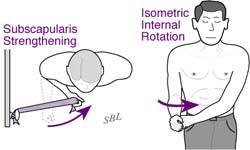

Exercises

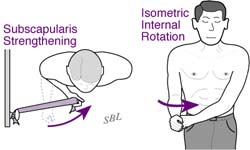

Shoulder exercises to strengthen the rotator cuff, such as those shown in Figure 12 above, may help control an unstable shoulder. Particularly in atraumatic instability, rotator cuff strengthening and training the shoulder for stability are the mainstays of treatment.

In traumatic instability, the repair of the labrum and the ligaments can usually restore stability to the joint. The restoration of stability often allows patients to return to their usual activities.

In atraumatic instability, there is no single lesion to repair. Thus, if exercises do not restore joint stability, careful consideration needs to be given to the advisability of any surgical procedure. While tightening or burning the ligaments and capsule of the joint have been used for this condition, it is recognized that these procedures may not specifically address the cause of the instability.

Surgery

Possible benefits of surgical repair for shoulder dislocations

The effectiveness of any surgical procedure depends on the health and motivation of the patient, the condition of the shoulder, and the expertise of the surgeon. When performed by an experienced surgeon, surgery for shoulder instability usually leads to improved shoulder comfort and function. This is particularly the case for individuals with traumatic instability where the injury can be specifically repaired. The greatest improvements are in the ability of the patient to sleep, to perform activities of daily living, and to engage in recreational activities.

Goal of surgery

Surgery to repair instability can help restore the function and comfort of unstable and dislocating shoulders. The goal of surgery for traumatic anterior instability is to repair the ligaments and the labrum that are torn from the lower front part of the glenoid socket. The opportunity for a secure and anatomic repair is best when the repair is done through open (not arthroscopic) surgery. As shown in Figure 13, the incision is made in the normal skin creases around the shoulder leaving a minimal surgical scar.

Surgery for traumatic vs. atraumatic instability

Figure 14 shows how ligaments and the labrum can be anatomically repaired so that their function is restored. If there is a substantial loss of the bone of the anterior glenoid lip, this can be restored by fixing a bone graft from the iliac crest (hip bone at the belt line) outside the shoulder joint capsule.

When performed by an experienced shoulder surgeon, surgery for traumatic anterior instability has an excellent chance of restoring stability to the shoulder.

For traumatic posterior instability, a similar repair can be carried out through an incision over the back of the shoulder.

For atraumatic instability, exercises are the first choice in treatment. When these are not successful, the surgical approach needs to be tailored to the specific circumstances. If the primary direction of atraumatic instability is posterior, a posterior glenoid osteoplasty provides a robust reconfiguration of the shape of the glenoid so that it provides additional stability. For multidirectional instability, a procedure to build up the glenoid labrum may increase the effective concavity of the glenoid socket. For patients with ligamentous hyperlaxity (excessive range of motion of the shoulder), a ligament and capsule tightening procedure is considered. This has been done with open surgery (known as a capsular shift) and by arthroscopic surgery (for example by burning and scarring the capsule).

Who should consider surgical repair for shoulder dislocations?

Surgery is considered for patients with:

- recurrent instability or feelings of unsteadiness or apprehension after a traumatic shoulder dislocation or

- atraumatic instability that has not responded to a well-conducted rehabilitation program.

Surgical options

For traumatic anterior shoulder instability, the most dependable results have been obtained with an open (not arthroscopic) repair that securely restores the attachment of the labrum and the ligaments to the edge of the glenoid socket as shown in Figure 15.

While arthroscopic approaches to surgical repair have been developed, the chance of persistent instability is less when the repair is carried out by open surgery. This may be due to the increased difficulty in restoring the normal anatomy and in achieving a secure repair using arthroscopic surgery. The return to activities after open surgery is at least as fast as with arthroscopic repair. The cosmetic appearance of the shoulder after open surgery done through the natural skin creases is at least as good as that after arthroscopic repair.

For shoulders in which the bone of the anterior (front) lip of the glenoid socket is lacking bone, grafting can be used to restore the configuration of the socket.

For shoulders in which the back of the socket is too flat, a reshaping of the socket (posterior glenoid osteoplasty) can be used.

For shoulders in which the soft tissues provide insufficient stability to the shoulder procedures can be considered to tighten the ligaments and capsule and to thicken the glenoid labrum (the "O" ring that surrounds the surface of the socket).

Effectiveness of surgery

In the hands of an experienced surgeon, repair for recurrent traumatic instability has an excellent chance of restoring much of the lost comfort and function to the unstable shoulder. With a good rehabilitation effort and with the avoidance of additional injuries, the result of the surgery should last for a long time.

The results of surgery for the more unusual types of instability depend on the specifics of the shoulder problem and the type of surgery performed. Patients should discuss the details of the problem and the proposed procedure with the surgeon.

Urgency and Timing of Surgery

Surgery for instability is not an emergency. Such a repair is an elective procedure that can be scheduled when circumstances are optimal. The patient has time to become informed and to select an experienced surgeon.

Before surgery is undertaken the patient needs to:

- be in optimal health

- understand and accept the risks and alternatives of surgery and

- understand the post operative rehabilitation program.

Surgery for shoulder instability can be delayed until the time that is best for the patient's overall well-being.

Surgery for shoulder instability should be performed when conditions are optimal. Particularly in the case of atraumatic instability, an extended effort at non-operative management is suggested. This is because there is not a specific surgical repair for a specific injury. On the other hand, in the case of recurrent instability or apprehension after an injury, surgery can be performed whenever it becomes evident that exercises are not effective in restoring the shoulder's ability to function. Usually a 6- to 12-week try at strengthening exercises is sufficient to determine whether exercises are likely to be effective.

Risks of surgery

The risks of surgery for shoulder instability include but are not limited to the following:

- infection

- injury to nerves and blood vessels

- inability to carry out the planned repair

- stiffness of the joint

- tear of the rotator cuff

- pain

- persistent instability

- the need for additional surgeries

There are also risks associated with anesthesia including death. An experienced shoulder surgery team will use special techniques to minimize these risks but cannot totally eliminate them.

Managing Surgical Risk

Many of the risks of surgery for instability can be effectively managed if they are promptly identified and treated. Infections may require a wash out in the operating room and subsequent antibiotic treatment. Blood vessel or nerve injury may require repair. Stiffness may require exercises or additional surgery. Persistent instability may require the consideration of additional surgery.

If the patient has questions or concerns about the course after surgery the surgeon should be informed as soon as possible.

Preparing for Surgery

Surgery for instability is considered for healthy and motivated individuals in whom shoulder dislocations or apprehension interfere with shoulder function. Successful surgery for instability depends on a partnership between the patient and the experienced shoulder surgeon. The patient's motivation and dedication are important elements of the partnership. Patients should optimize their health so that they will be in the best possible condition for this procedure. Smoking should be stopped a month before surgery and not resumed for at least three months afterwards--ideally never. This is because smoking interferes with healing of the repair. All heart, lung, kidney, bladder, tooth, or gum problems should be managed before surgery. Any infection may be a reason to delay the operation.

The patient's shoulder surgeon needs to be aware of all health issues, including allergies and non-prescription and prescription medications being taken. Some of these may need to be modified or stopped. For instance, aspirin and anti-inflammatory medication may affect the way the blood clots. The skin around the shoulder must be clean and free from sores and scratches.

Before surgery, patients should consider the limitations, alternatives, and risks of surgery. Patients should also recognize that the result of surgery depends in large part on their efforts in rehabilitation after surgery.

The patient needs to plan on being less functional than usual for up to twelve weeks after the shoulder repair. Lifting, pushing, pulling, and some activities of daily living can place stresses on the repair. Performing usual work or chores may be difficult during this time. Plans for necessary assistance need to be made before surgery. For people who live alone or those without readily available help arrangements for home help should be made well in advance.

The shoulder surgeon should answer any questions about the surgery or the recovery period.

Costs

- the surgeon's fee and

- the hospital fee.

Finding an experienced surgeon

Surgery for instability is a technically demanding procedure that is ideally performed by an experienced shoulder surgeon in a medical center accustomed to performing these procedures at least several times a month. Patients should inquire as to the number of instability repairs that the surgeon performs each year and the number of these procedures performed in the medical center each year.

Surgeons specializing in shoulder instability surgery may be located through university schools of medicine county medical societies state orthopedic societies or professional groups such as the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Society which offers a worldwide directory of shoulder and elbow surgeons on its web site.

Facilities

Surgery for shoulder instability is often performed in a major medical center that performs these procedures on a regular basis. These centers have surgical teams and facilities specially designed for this type of surgery. They also have nurses and therapists who are accustomed to assisting patients in their recover from this type of surgery.

Technical details

Shoulder instability surgery is a highly technical procedure; each step plays a critical role in the outcome. After the anesthetic has been administered and the shoulder has been prepared, a cosmetic incision is made in a natural skin crease at the front of the shoulder as shown in figure 16.

This incision allows access to the seam between the deltoid and the pectoralis major muscles. Splitting this seam allows access to the shoulder without detaching or damaging the important deltoid muscle, which is responsible for a significant portion of the shoulder's power. All scar tissue is removed from the space beneath the deltoid.

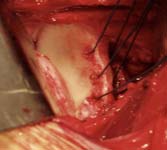

The tendon of the subscapularis muscle is incised (See Clip 6 - Subscapularis Incision) providing excellent access to the interior of the shoulder joint and a view of the detachment of the labrum and ligaments from the glenoid socket (See Clip 7 - Bankart Repair) as shown in Figure 17.

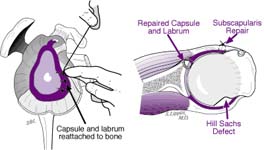

The goal of the repair is to reattach securely the labrum and ligaments to the area from which they were torn. This is accomplished by roughening the edge of the glenoid socket (See Clip 8 - Rough Lip) and drilling smdall holes through its lip in the area of the tear (See Clip 9 - Glenoid Holes). Passing suture (surgical thread) through these holes (See Clip 10 - Glenoid Suture) and then through the detached labrum and ligaments (See Clip 11 - Labrum Suture) restores the anatomy of the shoulder and the depth of the glenoid socket when the suture are tied as shown in Figure 18.

At the conclusion of the repair the subscapularis tendon is repaired anatomically as shown in Figure 18 and Clip 12 - Subscapularis Repair.

A cosmetic closure of the skin incision is carried out, dressings are applied, and the arm is placed in a sling.

Anesthetic

Shoulder instability surgery may be performed under a general anesthetic or a brachial plexus nerve block. A brachial plexus block can provide anesthesia for several hours after the surgery. The patient may wish to discuss their preferences with the anesthesiologist before surgery.

Length of surgical repair for shoulder dislocations

The procedure usually takes approximately one hour but the preoperative preparation and the postoperative recovery may add several hours to this time. Patients often spend two hours in the recovery room and about two days in the hospital after surgery.

Pain and pain management

Recovery of comfort and function after shoulder instability surgery continues for many months. Shoulder instability surgery is a major surgical procedure that involves cutting of skin, removal of scar tissue, and suturing of tendons and bone. The pain from this surgery is managed by the anesthetic and by pain medications. Immediately after surgery, strong medications (such as morphine or Demerol) are often given by injection. Within a day or so oral pain medications (such as hydrocodone or Tylenol with codeine) are usually sufficient.

Initially pain medication is administered usually intravenously or intramuscularly. Sometimes patient controlled analgesia (PCA) is used to allow the patient to administer the medication as it is needed. Hydrocodone or Tylenol with codeine are taken by mouth. Intravenous pain medications are needed usually for only the first day or two after the procedure. Oral pain medications are needed usually for only the first two weeks after the procedure.

Pain medications can be very powerful and effective. Their proper use lies in the balancing of their pain relieving effect and their other less desirable effects. Good pain control is an important part of the postoperative management.

Pain medications can cause drowsiness, slowness of breathing, difficulties in emptying the bladder and bowel, nausea, vomiting, and allergic reactions. Patients who have taken substantial narcotic medications in the recent past may find that usual doses of pain medication are less effective. For some patients, balancing the benefits and side effects of pain medication is challenging. Patients should notify their surgeon if they have had previous difficulties with pain medication or pain control.

Hospital stay

After surgery, the patient spends about an hour in the recovery room. A drainage tube is sometimes used to remove excess fluid from the surgical area. The drain is usually removed on the second day after surgery. Bandages cover the incision. They are usually changed the second day after surgery.

Hospital discharge

Patients are discharged as soon as:

- the incision is dry

- the shoulder is comfortable with oral pain medications

- the patient can perform the range of motion exercises

- the patient feels comfortable with the plans for managing the shoulder and

- the home support systems for the patient are in place.

Discharge is usually on the second day after surgery.

Patient limitations

Early, protected motion after shoulder instability surgery is helpful for achieving optimal shoulder function. Depending on the nature of the procedure, the surgeon will often prescribe some gentle motion exercises within a limited range of movement.

Walking and use of the arm for gentle activities (with the elbow at the side) are often encouraged soon after surgery, but the surgeon should be consulted for the specifics of each individual case.

Gentle activities of daily living are often permitted with the operated arm. However, lifting anything heavier than a cup of coffee or using the arm for forceful activities must avoided for six to twelve weeks depending on the procedure.

The surgeon often wishes to check the mobility of the shoulder two or three weeks after surgery to assure that the shoulder has not become too stiff.

Management of the patient's limitations requires advance planning to accomplish the activities of daily living during the recovery period. Patients may require some assistance with self-care activities of daily living, shopping, and driving for about one month after surgery.

Recovery of comfort and function after shoulder instability surgery continues for many months after the surgery. Improvement in some activities may be evident as early as three months. With persistent effort, patients make progress for as long as a year after surgery.

Physical therapy

A progressive rehabilitation program after instability surgery is critical for achieving optimal shoulder function.

Instable shoulders may become stiff after surgery. Early, protected motion is often suggested to prevent the shoulder from becoming stiff. However, the repair needs to be protected from re-injury. especially during the healing period. Thus, the surgeon will often prescribe limited early motion for three to six weeks and then strengthening exercises for a second six-week period.

Rehabilitation options

It is often most effective for patients to carry out their own exercises so that they are done frequently, effectively and comfortably. Usually a physical therapist or the surgeon instructs the patient in the exercise program and advances it at a rate that is comfortable for the patient.

For the first six weeks after surgery, emphasis is placed on protected motion. For the second six weeks, emphasis is placed on strengthening exercises so that strong muscles will protect the shoulder as it returns to normal activities.

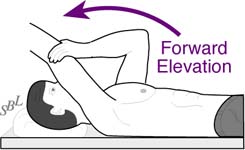

Figures 19 and 20, below, show examples of some of the exercises that may be used to develop strength and flexibility after the first six weeks following surgery; however, the surgeon must be consulted for the specifics on each case.

Once the range of motion and strength goals are achieved, the exercise program can be cut back to a minimal level. However, gentle stretching is recommended on an ongoing basis.

Patients are almost always satisfied with the increases in range of motion, comfort, and function that they achieve with the exercise program. If the exercises are uncomfortable, difficult, or painful, the patient should contact the surgeon promptly.

Stressful activities and activities with the arm in extreme positions must be avoided until healing is almost complete--often for three months after the surgery.

In general, the exercises are best performed by the patient at home. Occasional visits to the surgeon or therapist may be useful to check the progress and to review the program.

The surgeon and therapist should be able to provide the information on the usual cost of the rehabilitation program. The program is quite cost-effective because it is heavily based on home exercises.

This is a safe rehabilitation program with little risk.

Returning to ordinary daily activities

In general, patients are able to perform gentle activities of daily living with the operated arm at the side starting two to three weeks after surgery. Walking with the arm protected is strongly encouraged. Driving should wait until the patient can perform the necessary functions comfortably and confidently. This may take up to one month if the surgery has been performed on the right shoulder because of the increased demands on the right shoulder for shifting gears.

With the consent of their surgeon, patients can often return to activities such as swimming, golf, and tennis at six weeks after their surgery.

Patients should avoid activities that involve major impact (chopping wood, contact sports, sports with major risk of falls) or heavy loads (lifting of heavy weights, heavy resistance exercises) until three months after surgery and until the shoulder has excellent strength and range of motion--essentially equivalent to the opposite side. In this way the risk of re-injury is minimized.

Summary of surgical repair for shoulder dislocations for shoulder dislocations

Shoulder instability surgery can help restore comfort and function to shoulders with dislocations, instability, or apprehension. In the hands of an experienced surgeon, shoulder instability surgery can be a most effective method for restoring comfort and function to a shoulder with recurrent instability, dislocations, or apprehension in a healthy and motivated patient. The best results are obtained when the surgery repairs a shoulder injury which resulted in a tear of the labrum and ligaments from the glenoid socket. In this situation, the surgeon has a good opportunity to restore the normal anatomy of the shoulder. Pre-planning and persistent rehabilitation efforts will help assure an optimal result for the patient.

References:

Churchill R. S. M. Moskal et al. (2001) "Extracapsular Anatomically Contoured Anterior Glenoid Bone Grafting for Complex Glenohumeral Instability." Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery. 2(3):210-218.

Gibb T. D. J. A. Sidles et al. (1991). "The effect of capsular venting on glenohumeral laxity." Clin Orthop Relat Res(268): 120-7.

Harryman D. T. 2nd J. A. Sidles et al. (1990). "Translation of the humeral head on the glenoid with passive glenohumeral motion." J Bone Joint Surg Am 72(9): 1334-43.

Harryman D. T. 2nd J. A. Sidles et al. (1992). "The role of the rotator interval capsule in passive motion and stability of the shoulder." J Bone Joint Surg Am 74(1): 53-66.

Jackins S. and F. A. Matsen 3rd (1994). "Management of shoulder instability." J Hand Ther 7(2): 99-106.

Lazarus M. D. J. A. Sidles et al. (1996). "Effect of a chondral-labral defect on glenoid concavity and glenohumeral stability. A cadaveric model." J Bone Joint Surg Am 78(1): 94-102.

Lenters T. R. A. K. Franta et al. (2007). "Arthroscopic compared with open repairs for recurrent anterior shoulder instability. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature." J Bone Joint Surg Am 89(2): 244-54.

Lippitt S. and F. Matsen (1993). "Mechanisms of glenohumeral joint stability." Clin Orthop Relat Res(291): 20-8.

Matsen F. A. 3rd (1991). "Capsulorrhaphy with a staple for recurrent posterior subluxation of the shoulder." J Bone Joint Surg Am 73(6): 950.

Matsen F. A. 3rd (2002). "The biomechanics of glenohumeral stability." J Bone Joint Surg Am 84-A(3): 495-6.

Matsen F. A. 3rd C. Chebli et al. (2006). "Principles for the evaluation and management of shoulder instability." J Bone Joint Surg Am 88(3): 648-59.

Matsen F. A. 3rd C. M. Chebli et al. (2007). "Principles for the evaluation and management of shoulder instability." Instr Course Lect 56: 23-34.

Matsen F. A. 3rd D. T. Harryman 2nd et al. (1991). "Mechanics of glenohumeral instability." Clin Sports Med 10(4): 783-8.

Matsen F. A. 3rd and J. D. Zuckerman (1983). "Anterior glenohumeral instability." Clin Sports Med 2(2): 319-38.

Matsen L. J. C. Hettrich et al. (2006). "Direct injection of blood into the labrum enhances the stability provided by the glenoid labral socket." J Shoulder Elbow Surg 15(6): 651-8.

Metcalf M. H. D. G. Duckworth et al. (1999). "Posteroinferior glenoplasty can change glenoid shape and increase the mechanical stability of the shoulder." J Shoulder Elbow Surg 8(3): 205-13.

Montgomery W. H. Jr. M. Wahl et al. (2005). "Anteroinferior bone-grafting can restore stability in osseous glenoid defects." J Bone Joint Surg Am 87(9): 1972-7.

Schiffern S. C. R. Rozencwaig et al. (2002). "Anteroposterior centering of the humeral head on the glenoid in vivo." Am J Sports Med 30(3): 382-7.

Shuman W. P. R. F. Kilcoyne et al. (1983). "Double-contrast computed tomography of the glenoid labrum." AJR Am J Roentgenol 141(3): 581-4.

Thomas S. C. and F. A. Matsen 3rd (1989). "An approach to the repair of avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments in the management of traumatic anterior glenohumeral instability." J Bone Joint Surg Am 71(4): 506-13.

von Eisenhart-Rothe R. F. A. Matsen 3rd et al. (2005). "Pathomechanics in atraumatic shoulder instability: scapular positioning correlates with humeral head centering." Clin Orthop Relat Res(433): 82-9.

Zuckerman J. D. and F. A. Matsen 3rd (1984). "Complications about the glenohumeral joint related to the use of screws and staples." J Bone Joint Surg Am 66(2): 175-80.