Treating Shoulder Dislocation / Subluxation (Instability) and Associated Pain with Minimally Invasive Arthroscopy

Last updated: Monday, January 28, 2013

Overview

Tears to the labrum cartilage and shoulder ligaments are common shoulder injuries, caused by a single traumatic event or by sustained overuse or wear of the shoulder joint. Such tears make the joint vulnerable to recurrent slipping, dislocation, and accompanying pain.

Cartilage repair and capsulorraphy (ligament repair and tightening) for tears is readily accomplished via arthroscopy, in which the surgeon manipulates instruments through a thin tube (cannula) inserted through a few small (1 cm) incisions in the patient’s skin. This allows the active person to experience a minimum of pain after surgery and get back to work quickly.

Recovery is fairly rapid, over a period of four weeks for most daily tasks – though athletes must wait several months before resuming weight training for sports activities. The surgery has a high success rate – in the 90 percent range.

The arthroscopic technique presents a less-invasive alternative to the “open” approach, which for years has been the standard technique for all shoulder surgeries. In this approach, the surgeon makes a longer (10 cm) vertical incision to the patient’s shoulder, above the armpit. The bigger incision gives easy visual access to the joint and surrounding tissues – but requires the surgeon to divide tendons to gain instrument access to the joint.

With arthroscopic repair, a series of three or four small (1 cm) incisions around the shoulder gives a surgeon minimally invasive access to the injured tissues. Fewer surgeons have significant experience with this technique, as it is more technically demanding. Data suggests that, for many shoulder procedures, an arthroscopic approach yields similarly positive patient outcomes as the open approach.

The bonuses of arthroscopic technique, if it is appropriate to the patient’s injury, are less postoperative pain and scarring. Additionally, no tendons are divided so the risk of late tendon weakness or failure is avoided.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

Characteristics of cartilage and ligament tears in the shoulder

Individuals with cartilage or ligament tears will have pain deep in the shoulder, especially with certain positions and with overhead activities, (e.g., throwing/hitting sports like softball, volleyball, and tennis; kayaking, surfing, weightlifting, climbing, painting, racquet sports, etc). They may experience a popping or clicking sound in the shoulder with motion that may or may not be painful. In some cases the popping seems to lessen the pain. Not uncommonly, the pain is mild during exercise, but becomes worse later that evening or the next day. Pain can emerge with specific actions such as cocking the arm to throw, or when the racquet meets the ball. The pain may lessen with rest, but recurs when the shoulder is put back in action. A shoulder slipping in and out of the socket suggests a more severe ligament tear. Partial slipping is called subluxation, while complete disassociation of the shoulder joint is called dislocation (Figure 1). Dislocations may require an individual to have assistance to relocate, or reduce, the shoulder joint (Figure 2). Some people who have had many dislocations become adept at relocating their shoulders without assistance by gently manipulating it. However, the “Martin Riggs” (Mel Gibson in the “Lethal Weapon” movies) method of reduction –violently slamming it into place – is not recommended as it can actually worsen the injury. Others have been told, erroneously, that they will have to live with their “trick shoulder” or undergo a major operation, so they elect to live with the condition.

Types

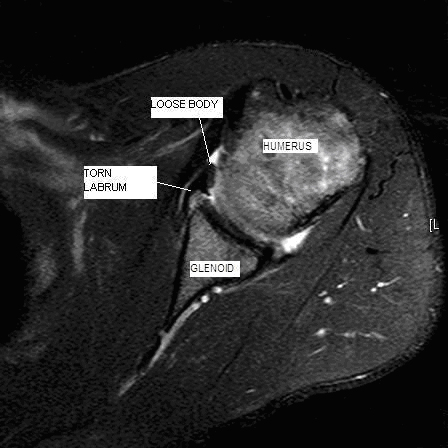

Cartilage tears have many names based on their location in the shoulder joint. Most involve the labrum, an “O ring”-like structure that runs along the circumference of the shoulder socket (glenoid). The labrum effectively deepens the glenoid and serves as a point of attachment for ligaments of the shoulder and the biceps tendon (Figure 3). Tears on the upper half of the labrum are commonly called SLAP – Superior Labrum Anterior (front) to Posterior (back) – tears. These tears (Figure 4) can present with popping or catching sensations within the shoulder. Sometimes by moving the shoulder a certain way, an individual can make the shoulder feel as the tear temporarily falls back in place. Unfortunately, these tears do not heal on their own.

Tears in the lower half of the labrum usually involve the ligaments in the front or back of the shoulder (Figure 5). This allows the ball (humeral head) to move too far from the glenoid in one or both directions, and creates instability.

Similar conditions

Tears of the shoulder’s labrum and capsule might be confused with – and must be distinguished from – rotator cuff tears, “frozen shoulder” (adhesive capsulitis) and shoulder or neck arthritis – each of which may produce somewhat similar symptoms. Rotator cuff tears usually cause pain and weakness. Frozen shoulder is characterized by shoulder stiffness, but X-rays usually are normal. Shoulder arthritis is most often associated with some stiffness and popping. Neck arthritis may cause shoulder pain and weakness that can be worse when the head is held in certain positions. An experienced shoulder surgeon can discern what is causing the patient’s pain or shoulder instability with a careful history and physical exam.

Incidence and risk factors

Tears of the labrum and shoulder capsule are very common in active people who engage in vocational or recreational activities that demand upper body use. Tears can occur when the arm is forcefully moved into an abnormal position, placing excess stress on the shoulder. People who participate in sports such as tennis, swimming, rowing, volleyball and baseball, in which the shoulder is used repetitively, are more at risk. Action-sports athletes (snowboarders, skiers, skateboarders, surfers and motor-sports enthusiasts) are also at risk for these injuries. People whose jobs require frequent overhead lifting or movement are at increased risk. An external trauma, such as a fall onto an outstretched arm or onto the shoulder, is another way in which these structures are injured among the general population.

Diagnosis

When a patient presents with a shoulder problem, a doctor’s initial diagnostic technique includes the patient’s oral history and physical examination. Specific questions about a patient’s mechanism of injury or background of activity will lend clues. Specific physical tests are performed to pinpoint the cause of the problem.

X-rays of the shoulder are often typical. In some cases a magnetic resonance image (MRI) will be ordered, often requiring an injection of dye into the shoulder joint. This can highlight injuries to cartilage and ligaments.

However, MRIs can be read as “normal” in some cases when a subtle abnormality exists. Alternatively, an unusual cartilage appearance called a tear by a radiologist might be a normal variant or an incidental finding, when something else is causing the patient’s pain. In these cases, the history and physical exam in the hands of an experienced clinician are crucial to determining the cause of the pain/disability (Figure 6).

Treatments

Medications

Anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications may be helpful in managing the pain that accompanies torn cartilage or ligaments. However, they but do not change the course of the condition.

It is important that the patient be aware of the possible side effects of these medications, including stomach irritation, kidney problems and bleeding. Injections of steroids (cortisone) into the shoulder have not been demonstrated to have lasting benefit and carry some risk of infection.

For each medication, patients should learn the risks, possible interactions with other drugs, the recommended dosage, and the cost.

Exercises

No exercises are known to repair torn structures inside the shoulder. However, if exercises and stretching are not painful, they may be helpful in maintaining the flexibility and strength of joints with cartilage or ligament tears. In most cases, these exercises can be done in the patient's home with minimal equipment. Shoulder exercises are best performed several times a day on an ongoing basis with gradual increases in resistance. Any exercise that is painful should be avoided, as “no pain, no gain” does not apply in a rehabilitation setting.

Often the exercises will help during the earlier phases of the condition, reducing discomfort, occasionally to the point that no further treatment is needed.

Other therapies may be recommended by homeopathic and chiropractic practitioners. Patients should learn the anticipated effectiveness of those approaches, as well as the costs and possible risks.

Possible benefits of arthroscopic labral repair/capsulorraphy

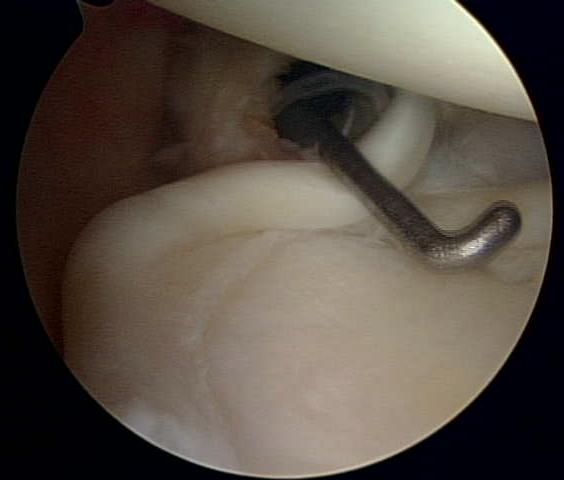

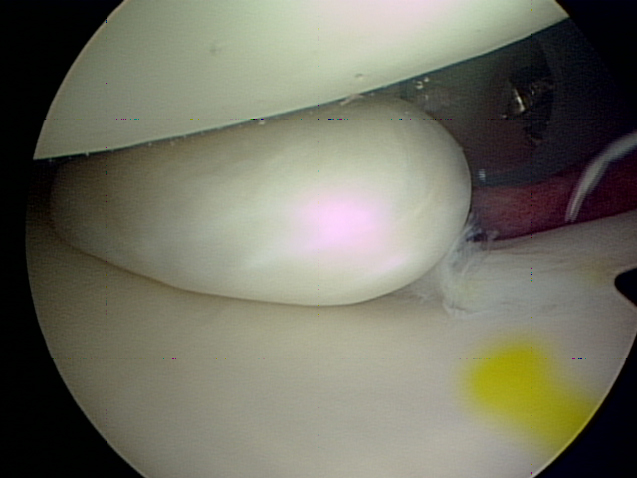

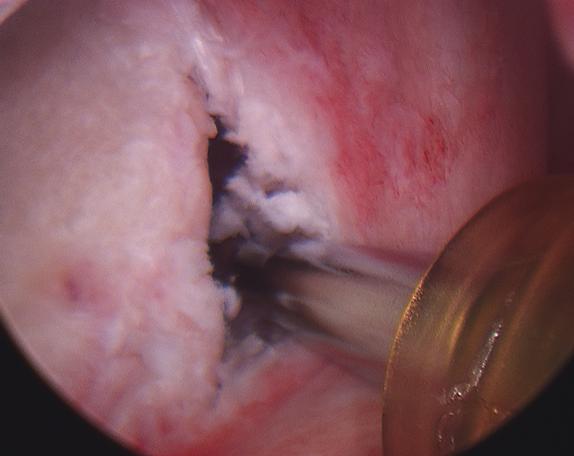

Repairing the torn cartilage of the labrum can increase the smoothness of the joint surfaces. Surgery can eliminate or greatly reduce the clicking and popping sensations that some patients experience. Loose pieces of cartilage or bone can also be identified and removed arthroscopically (Figures 7, 8).

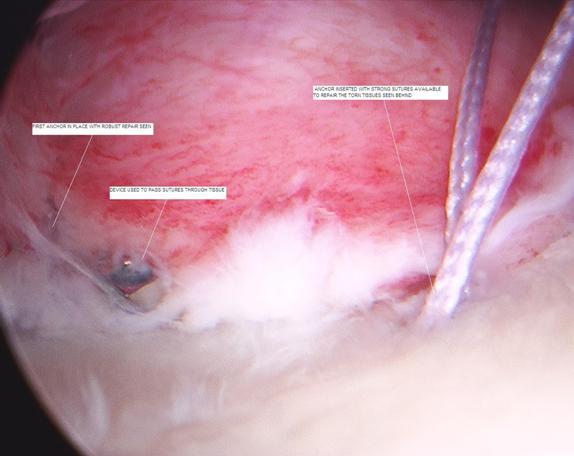

Repairing the torn labrum recreates the “bumper” at the edge of the socket, and decreases the ability of the humeral head to slide out of the joint (Figures 9, 10). Tightening of the ligaments in the capsule would diminish excessive motion of the shoulder joint, eliminating or reducing the likelihood of subluxation or dislocation. Overall this would increase the shoulder's stability.

Types of surgery recommended

Many patients with torn labrum or shoulder cartilage will benefit from arthroscopic repair. The procedures can be done concurrently, if needed; oftentimes the labral cartilage tears away from the bone but is still connected to the ligament. So when the cartilage is repaired, the ligament is tightened, as well.

Patients’ injuries might require an open procedure (using a larger incision than arthroscopy) to adequately stabilize the shoulder. Such injuries would include large, bony fractures of the glenoid socket (“bony Bankart lesions”), for instance.

Not all surgical cases are the same, this is only an example to be used for patient education.

Who should consider arthroscopic labral repair/capsulorraphy?

Arthroscopic repair is appropriate and usually effective for a patient whose pain and/or instability suggests a torn cartilage and/or capsular ligament.

However, in cases of more substantive injury to the humerus or glenoid, or to surrounding bones, muscles or tendons, the surgeon might be more likely to recommend an open approach to the procedure.

What happens without surgery?

Without surgery, in the best-case scenario, the patient would adapt to the condition and any corresponding loss of motion, or satisfactorily change their lifestyle and activities. Pain and/or instability would plateau at a degree that the patient finds bearable, and the injury would not worsen.

In the worst-case scenario, the tear or tears worsen, causing more pain, or the ligament stretches more, making the shoulder less stable. Either of these conditions can damage the articular cartilage – the smooth, almost frictionless cartilage on the surfaces of the bones – and this can lead to arthritis. As well, frequent dislocations of the humerus can, over time, break down the outer edge of the glenoid socket, much as the top edge of a golf tee is worn down or chipped. This accelerates the frequency with which the humerus subluxates or dislocates from the glenoid with decreasing amounts of force, sometimes even occurring in their sleep.

Surgical options

The two main options are arthroscopic repair and open repair. The open technique for years has been the standard approach.The surgeon makes a longer (10 cm) vertical incision to the patient’s shoulder, above the armpit. The bigger incision gives easy visual access to the joint and its surrounding tissues but requires the surgeon to divide tendons to gain instrumental access to the joint.

This more invasive procedure is performed, appropriately, when the humerus or glenoid bones are severely damaged, or when large, bony fractures of the glenoid socket (“bony Bankart lesions”) exist. The open approach requires an overnight stay at the hospital after surgery. Postoperative pain can be greater for patients undergoing an open procedure.

With arthroscopic repair, a series of three or four small (1 cm) incisions around the shoulder gives a surgeon minimally invasive access to the injured tissues. Fewer surgeons have significant experience with this technique, as it is more technically demanding. Data suggests that, for many shoulder procedures, an arthroscopic approach yields similarly positive patient outcomes as the open approach.

The bonuses of arthroscopic technique, if it is appropriate to the patient’s injury, are less postoperative pain and scarring. Additionally since no tendons are divided, the risk of late tendon weakness or failure is avoided.

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of the arthroscopic procedure depends on the health and motivation of the patient, the condition of the shoulder, and the expertise of the surgeon. When performed by an experienced surgeon, arthroscopic labral repair and/or capsulorraphy usually provides improved shoulder comfort and function, and the patient ultimately can return to sports activities, if he or she desires.

The arthroscopic procedure’s success rate is above 90 percent. An experienced surgeon performing this repair can provide a patient with decades of reduced or no pain, and/or with much improved shoulder stability.

The open repair has had a longstanding, well-documented rate of success also above 90 percent. For traumatic anterior shoulder instability, the most dependable results have been achieved with an open repair. One trade-off is that the open repair is more likely to create residual minor stiffness.

The return to athletic activities after open surgery is at least as fast as with arthroscopic repair, but most patients return to work faster after the arthroscopic approach.

Urgency

Surgery for cartilage tears or instability is not an emergency. Labral repair or capsulorraphy are an elective outpatient procedure that can be scheduled when circumstances are optimal. The patient has time to become informed and to select an experienced surgeon.

It is advisable to consider surgical repair even after a first-time dislocation. Recurrent instability occurs variably but is more frequent in young, aggressive athletes; that population has a rate of recurrence above 80 percent. Older, more sedentary people have lower rates of repeat dislocation. While the traditional wisdom has been to wait-and-see whether instability becomes a recurrent problem, each patient should make the decision about surgery based on available information. For example, a traditional weekend athlete who plays pickup ball might decide to wait-and-see, but the kayaker, skydiver or rock-climber might be at considerably more risk with a sudden re-dislocation in a precarious situation.

Before surgery is undertaken, the patient needs to be in optimal health, understand and accept the risks and alternatives of surgery, and understand the postoperative rehabilitation program.

Surgery should be performed when conditions are optimal. In some cases, particularly with non-traumatic instability, an extended effort at non-operative management is suggested. Usually a six- to twelve-week attempt at strengthening exercises is sufficient to determine whether exercises are likely to be effective. However, in many cases, therapy will strengthen the surrounding muscles and improve function, though it will not heal the torn tissues.

Risks

The complications of arthroscopic shoulder surgery for cartilage and ligament tears are infrequent. Risks include but are not limited to the following: infection, injury to cartilage, nerves and blood vessels, fracture, stiffness or recurrent instability of the joint, pain, blood clots and the need for additional surgeries. There are also risks in having anesthesia and the administration of a variety of medications. Blood clots in the legs (deep venous thrombosis, or DVT) can form and travel to the lungs and make breathing difficult. This is also very rare unless the patient has a predilection to clotting.

An experienced shoulder surgical team will use special techniques to minimize these risks, but cannot totally eliminate them.

Managing risk

Many risks of shoulder arthroscopic surgery for cartilage and ligament tears can be effectively managed if they are promptly identified and treated. Infections, while rarely seen, may be treated with antibiotics or require a cleansing in the operating room.

Injuries to nerves or blood vessels are exceedingly rare, but may require repair. DVTs are usually treated with medications.

Preparation

Shoulder labral repair and capsulorraphy surgery is considered for healthy and motivated individuals for whom the pain and vulnerability to dislocation interferes with desired shoulder function.

Successful surgery depends on a partnership between the patient and the experienced shoulder surgeon. Patients should optimize their health so that they will be in the best possible condition for this procedure. Smoking should be stopped a month before surgery and not resumed for at least three months afterward (if ever). Any heart, lung, kidney, bladder, tooth, or gum problems should be managed before surgery. Any infection may be a reason to delay the operation. The shoulder surgeon needs to be aware of all health issues, including allergies and the non-prescription and prescription medications being taken. Some of these may need to be modified or stopped. For instance, aspirin and anti-inflammatory medication may affect the way the blood clots.

The area of skin that will be involved in the surgery must be clean and free from sores and scratches.

Before surgery, patients should consider the limitations, alternatives and risks of surgery. Patients should also recognize that the result of surgery depends in large part on their efforts in rehabilitation after surgery.

Postoperatively, the patient needs to plan on being less functional than usual for six to twelve weeks. Driving, shopping and performing usual work or chores may be difficult during this time. Plans for necessary assistance need to be made before surgery. For individuals who live alone or those without readily available help, arrangements for home help should be made well in advance.

Timing

Shoulder labral repair and capsulorraphy can be delayed until the time that is best for the patient's overall well-being. However, in cases of recurrent catching or instability, excessive delays can result in the loss of bone and cartilage. These losses can complicate the surgical procedure and can compromise the quality of the surgery as well as its result.

Costs

The patient’s insurance provider should be able to provide a reasonable estimate of the surgeon's fee, the hospital fee, and the degree to which these are covered by insurance.

Surgical team

Shoulder stabilization, particularly when done arthroscopically, is a technically-demanding procedure that should be performed by an experienced, specially-trained shoulder surgeon in a medical center. Your surgeon should be performing complex arthroscopic shoulder procedures on a weekly basis. Patients should inquire about the surgeon’s specific training for such procedures (e.g., fellowship training in sports medicine) to become a specialist familiar with arthroscopic techniques and equipment. Patients might also ask how many of these procedures the surgeon and the medical center perform on a yearly basis.

Finding an experienced surgeon

Surgeons who are capable of performing simple arthroscopic procedures are readily available in the community. However, complex reconstructive surgeries in the shoulder (e.g., arthroscopic stabilization procedures, arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs) demand highly-specialized training. Most capable surgeons will have completed a fellowship, (additional year or two of training) specifically in arthroscopic techniques, shoulder surgery and sports medicine.

A qualified sports medicine surgeon should be comfortable with both open and arthroscopic techniques, and tailor the appropriate treatment to the problem to be addressed. Fellowship-trained surgeons can be located through university schools of medicine, county medical societies, state or national orthopedic societies. Other resources include professional societies such as the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) or the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeon’s Society (ASES).

Facilities

Arthroscopic labral repair and capsulorraphy are usually performed in qualified ambulatory surgical centers or major medical centers where such procedures are common. These centers have surgical teams, facilities, and equipment specially designed for this type of surgery. For those patients who must stay overnight, the medical centers have nurses and therapists who are accustomed to assisting patients in their recovery from shoulder surgery.

Technical details

During arthroscopic shoulder surgery, the patient is on his side, with the damaged shoulder exposed upward and its arm out slightly from the body. After the general anesthetic is administered and the shoulder is prepared, the surgeon makes three or four 1 cm incisions, two at the anterior shoulder and one or two at the posterior. Incisions would be slightly above the axilla (armpit).

Cannulas (5 mm to 8 mm diameter) are plastic tubes inserted into these incisions, functioning as portals through which the surgeon passes the arthroscope, instruments and sutures. The arthroscope can extend approximately 3 inches inside the patient.

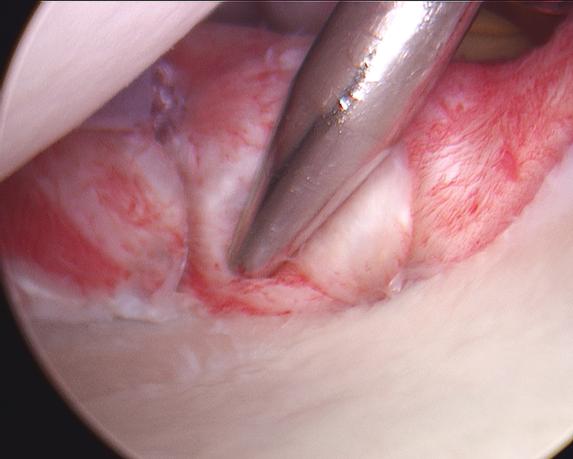

The surgeon first mobilizes the muscles and other tissues near the shoulder by removing any scar tissue which has accumulated and which may be preventing cartilage from reattaching to the bone (Figure 11). To repair the labrum, the surgeon will stimulate the glenoid bone by lightly rasping it, then must insert three or four tiny, moly-bolt-like anchors into the glenoid’s rim where the cartilage has been torn away (Figure 12). Holes for the anchors are drilled in the glenoid using a 2.7 mm bit (Figure 13). The surgeon captures the cartilage and ligaments with the sutures, which are connected to the anchors (Figure 14).

For shoulders in which the soft tissues provide insufficient stability to the shoulder, capsulorraphy can tighten any of ligaments – the ones connecting the glenoid and humerus, and the attachments of the biceps tendon to the bone. To tighten the ligaments, the surgeon will sometimes take a tuck in the ligament, slightly folding it over itself, and suturing it in a shortened form.

In the open approach, the surgery is much the same, though the surgeon must first divide the subscapularis tendon on the anterior shoulder to reach the capsule layer. (The arthroscopic approach goes between tendons instead of through them.)

Anesthetic

Arthroscopic labral repair and capsulorraphy may be performed under a general anesthetic or under a brachial plexus nerve block. A brachial plexus block can provide anesthesia for several hours after the surgery. The patient may wish to discuss their preferences with the anesthesiologist before surgery.

Length of arthroscopic labral repair/capsulorraphy

The arthroscopic shoulder repair procedure usually takes one to two hours, and the preoperative preparation and the postoperative recovery may add several hours to this time. Patients often spend an hour in the recovery room and are discharged the same day. In patients with other medical problems, or requiring more invasive surgeries may stay overnight in the hospital after surgery.

Pain and pain management

Pain from this surgery is managed by the anesthetic and by medications. With the arthroscopic approach, the patients would leave the hospital that day with a prescription for Vicodin or a similar narcotic, which could be expected to help them manage postoperative pain.

With the open approach, the patient is likely to experience more pain after surgery, and will have an intravenous drip pain reliever overnight and ice treatment into the next day. Sometimes patient-controlled analgesia is used to allow the patient to administer the medication. Within a day or so, the patient usually can be transitioned to oral pain medications such as hydrocodone or Tylenol with codeine.

Use of medications

In most cases pain relievers are prescribed for patients to take one to two weeks postoperatively.

Effectiveness of medications

Pain medications can be very powerful and effective. Their proper use lies in the balancing of their pain relieving effect and their other, less desirable effects. Good pain control is an important part of the postoperative management.

Important side effects

Pain medications can cause drowsiness, slowness of breathing, difficulties in emptying the bladder and bowel, nausea, vomiting and allergic reactions. Patients who have taken substantial narcotic medications in the recent past may find that usual doses of pain medication are less effective. For some patients, balancing the benefit and the side effects of pain medication is challenging. Patients should notify their surgeon if they have had previous difficulties with pain medication or pain control.

Hospital stay

For those patients who undergo the open shoulder-surgery approach, the patient spends an hour or so in the recovery room postoperatively. A drainage tube is sometimes used to remove excess fluid from the surgical area. The drain is usually removed on the day after surgery. Bandages cover the incision(s). They are usually changed two days after surgery.

Very rarely patients have complications from surgery, such as infection, that require a longer stay in the hospital.

Recovery and rehabilitation in the hospital

After surgery, some in-patients may see a physical therapist before being discharged in order to minimize the likelihood of scar tissue. Typically patients will start physical therapy in earnest after they are home.

Hospital discharge

At the time of discharge, the patient should be relatively comfortable on oral medications, should have a dry incision, should understand their exercises and should feel comfortable with the plans for managing the shoulder.

For the first month or so after this procedure, the shoulder on which surgery was performed may be less useful than it was immediately beforehand.

The specific limitations can be specified only by the surgeon who performed the procedure. The incision(s) must be kept clean and dry for the first week after surgery. It is important that the repaired structures not be challenged until they have had a chance to heal. Usually the patient is asked to lift little more than a cup of coffee for one month after surgery and wear a sling when up and about.

Convalescent assistance

After this shoulder surgery, patients will be in a sling for the better part of one month, so usually will require some assistance with self-care, activities of daily living, shopping and driving during that span. The range of motion with the lower arm is unrestricted. People may return to work the following week and resume tasks such as typing (removing their arm from the sling if need be) but should not put any load on the repaired shoulder.

Patients usually go home after this surgery, especially if there are people at home who can provide the necessary assistance.

Physical therapy

Early motion after shoulder surgery is helpful for achieving optimal shoulder function. A postoperative therapy protocol usually is set out a week at a time by either the physical therapist or surgeon. Initially stretching exercises are more important to regain range of motion and diminish the likelihood that scar tissue develops. Later, at four to six weeks, strengthening exercises can begin.

Rehabilitation options

It is often most effective for the patient to carry out his or her own exercises so that they are done frequently, effectively and comfortably. Usually, a physical therapist instructs the patient in the exercise program and advances it at a rate that is comfortable for the patient. After surgery, emphasis is initially on improving flexibility and range of motion of the shoulder through gentle stretching exercises. Three months postoperatively, a physical therapist could add strenuous exercises (e.g., weightlifting) to the protocol.

Can rehabilitation be done at home?

In general the exercises are best performed by the patient at home. Occasional visits to the surgeon or therapist may be useful to check the progress and to review the program.

Usual response

Patients are almost always satisfied with the increases in range of motion, comfort and function that they achieve with the exercise program. If the exercises are uncomfortable, difficult, or painful, the patient should contact the therapist or surgeon promptly.

Risks

This is a safe rehabilitation program with little risk. The main risk is failing to follow the therapy protocol, either by not doing exercises and stretching or by attempting to resume physical activities too quickly. Such activity or lack of activity could compromise the surgical result.

Duration of rehabilitation

Once the range of shoulder motion and strength goals are achieved, the exercise program can be cut back to a minimal level. However, gentle stretching is recommended on an ongoing basis.

Returning to ordinary daily activities

Patients could plan to resume daily light activities and tasks approximately one month after surgery, though probably could drive a stick-shift automobile sooner, at two weeks.

Athletes attempting to resume play will have to wait significantly longer; for example, no throwing should take place for three months postoperatively. Similarly, heavy training or a very physically demanding jobs, such as construction work, can be safely resumed three or four months after surgery.

Long-term patient limitations

Most shoulder-surgery patients can anticipate a full return to previous activities. No long-term limitations are anticipated.

Costs

The surgeon and therapist should provide the information on the usual cost of the rehabilitation program. The program is quite cost-effective, because it is based heavily on home exercises.

Summary of arthroscopic labral repair/capsulorraphy for cartilage and ligament tears in the shoulder

Repair of these shoulder structures – the labrum, capsule and ligaments – has shown to dramatically decrease the risk of recurring injuries.

Postoperative pain and disability from an arthroscopic approach can be far less than an open approach to shoulder surgery.

The art and science of orthopedic surgery has improved such that most people don't have to live with a "trick shoulder" or a shoulder that is unreliable.

Patients should be committed to slowing down for three to four months postoperatively to allow their soft tissues to heal to have the best surgical result. Planning to have assistance for daily tasks such as taking out trash and carrying groceries will help immensely.

Together as a team, the surgeon and the patient can create a surgical result that most patients find very satisfying.

127

Edited by:

Edited by: