Authors

John Allerdice-Seddon MS-4

Dan Heaston MD

Pete Scheffel MD

Erica Burns MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston J Warme MD

Frederick A Matsen III MD

Clinical Presentation

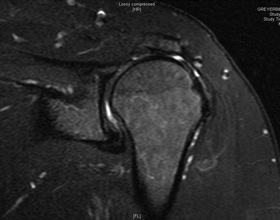

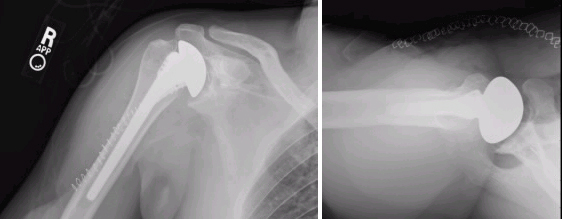

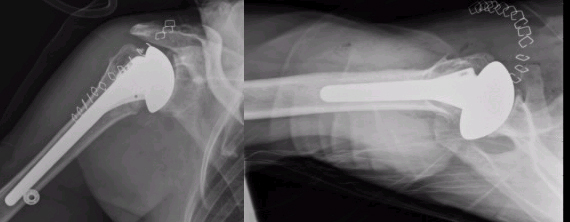

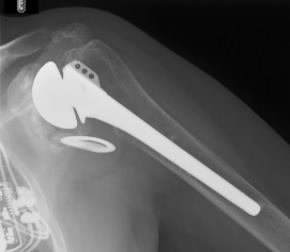

A 46 year-old right hand dominant female well known to the Bone and Joint clinic had a five-year history of pain and weakness in her left shoulder. The patient originally sustained a massive irreparable tear of her infraspinatus and supraspinatus tendons following a fall at her work. She underwent attempted rotator cuff repair at an outside facility shortly after her injury with minimal improvement in symptoms. After which she presented to the Bone and Joint clinic and was tried on an extensive course of non-operative management which was sustainable for four years until her symptoms worsened to the point that they were interfering with her activities of daily living. On physical examination the patient was able to achieve 80 degrees of forward elevation and -10 degrees of external rotation with positive external rotation lag sign and horn blowers sign. Her pre-operative X-rays (Fig. 1) and MRI demonstrate a massive rotator cuff tear of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons (Fig. 2) and possible minor tear of the superior subscapularis tendon.

Our concerns included:

- The patient’s inability to perform ADL’s.

- Close proximity of proposed muscle transfer to prominent nervous tissue.

- The health of the subscapularis tendon.

- The integrity of the transferred tendon repair post operatively.

- The need for absolute patient compliance of no shoulder ROM for 6weeks post-op.

Management

Two main treatment options were discussed with the patient:

- Continue non-operative treatment with physical therapy with the hope that she could regain some ability to externally rotate her arm.

- Operative treatment consisting of a tendon transfer procedure to recreate structures capable of external rotation.

These options were discussed thoroughly with the patient. She was adamant about attempting operative treatment as she had been attempting physical therapy for the previous four years and her function was continuing to decline. Appropriate surgical options in this case revolved around a latissimus dorsi tendon transfer procedure or a latissimus dorsi and teres major tendon transfer. We concluded that the procedure giving this patient the best chance of a positive functional outcome was a latissimus dorsi & teres major transfer procedure. It was a concern that solely transferring the latissimus dorsi might not give the patient enough strength in external rotation. The procedure was discussed thoroughly with the patient. She fully understood that this operation is not designed to return normal function to the shoulder. The goal of the procedure is to allow the patient to comfortably perform activities of daily living.

History

L’Episcopo performed the first latissimus dorsi/teres major tendon transfer procedure in 1934 to restore external rotation in pediatric patients that sustained obstetric plexus paralysis.1 L’Episcopo described a two-incision approach for this procedure. In 1988 Gerber was the first to report latissimus dorsi transfer in the setting of massive rotator cuff deficiency.2 He described the transfer of the latissimus dorsi tendon to the greater tuberosity of the humerus to mimic the native muscles of external rotation. Later Boileau et al described a single deltopectoral approach to the L’Episcopo procedure.3 4 In another modification Moursy et al found promising results by harvesting a small piece of bone along with the latissimus dorsi tendon to allow for transosseous fixation.5 The Moursy findings were based on the procedure used by Gerber et al. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer procedures are performed as a primary procedure for massive irreparable rotator cuff deficiency. They are also used as a salvage procedure for failed rotator cuff repairs. The goal of the procedure is to regain enough external rotation to perform ADL’s. With that in mind they are generally not attempted until a patient has negative external rotation (cannot rotate to a neutral position). It must be stressed with the patient that it is not a realistic goal to regain normal function of the shoulder with this procedure. Forward elevation is generally still decreased following this procedure. Modest gains in forward elevation can be seen as once the arm gets close to 90 degrees external rotation assists in raising it further however this is not the main goal of the operation. The procedure is not without its pitfalls as important neurovascular structures lay within the operative field namely the radial axillary and musculocutaneous nerves. Tendon transfer failure is also a concern as a large amount of force is applied to the repair with external rotation.5 Many negative prognostic factors have been described for this procedure including insufficient subscapularis advancing age female gender and transfer following attempted rotator cuff repair.2 5 6

Procedure

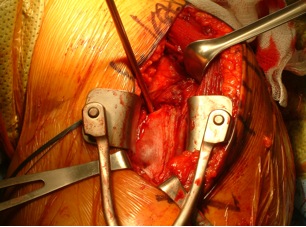

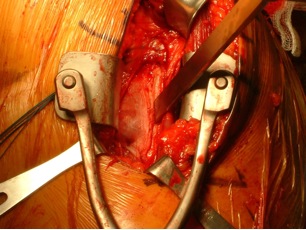

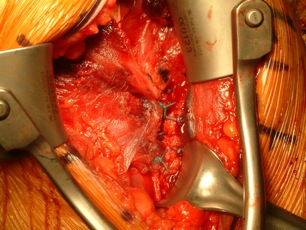

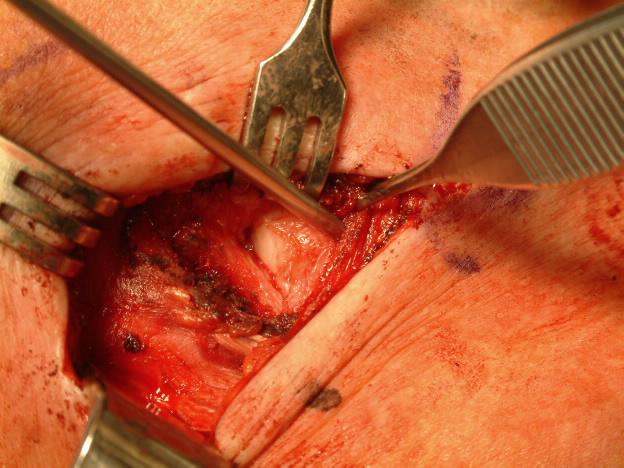

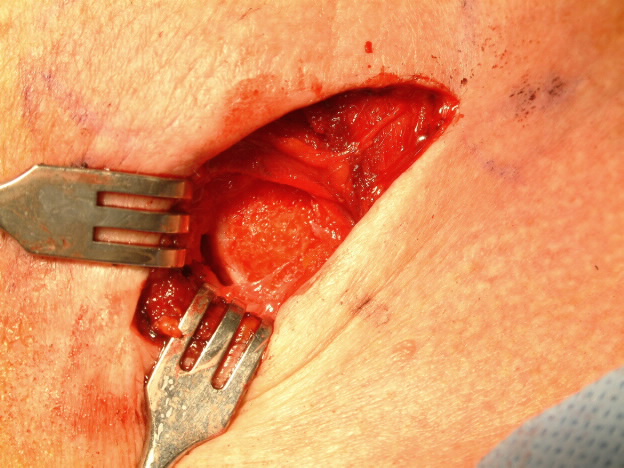

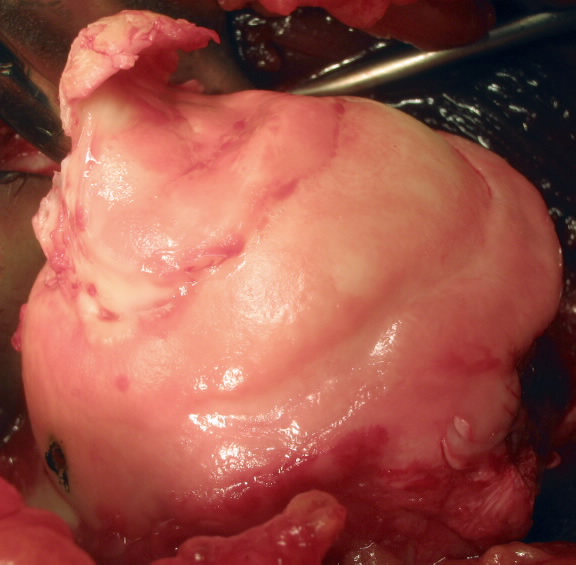

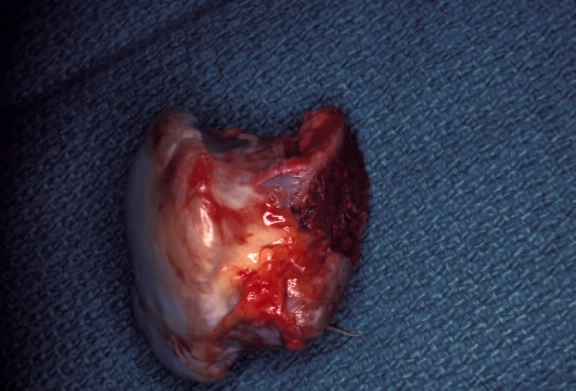

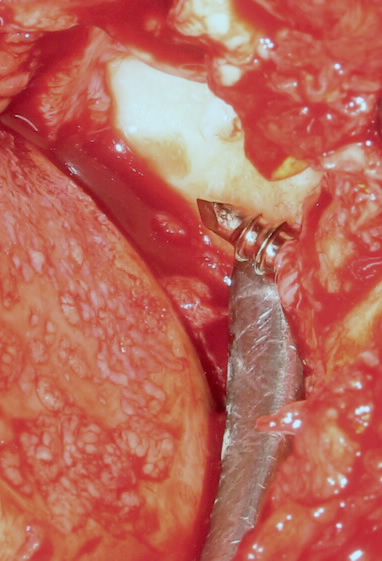

The patient was placed in a beach chair position and the left shoulder was properly draped. A single incision deltopectoral approach was utilized. The subscapularis tendon was visualized and remained intact which was a positive sign as the health of the subscapularis tendon was one of our original concerns. The pectoralis major tendon was detached reflected and tagged with three #3 Tevdek sutures leaving about 1cm stump for reapproximation later. We had good visualization of the latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons (Fig. 3). The insertion of the latissimus dorsi and teres major were cleaned and identified. At this point we attempted to remove a small piece of bone with insertion of these tendons to allow for transosseous fixation upon reapproximation5 (Fig. 4).

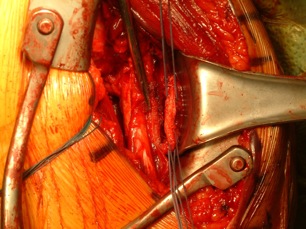

After the latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons were freed from the humerus they were sutured together using two #2 FiberWire and two #5 TiCron sutures with a Mason-Allen stitch.3 A tunnel was made posterior to the humerus by blunt dissection. The sutures attached to the latissimus dorsi/teres major tendon complex were passed posterior to the humerus using suture passers. Close attention was paid to the orientation of the transferred tendon twisting of the tendon could have disastrous effects. The visual field was limited at this point because the tendon was behind the humerus so this might not be obvious.

Once the tendon was successfully passed to the posterolateral aspect of the humerus it was approximated to the stump of the pectoralis major tendon (Fig. 5). Two biceps Endobuttons were placed in the humerus for increased stability of the transfer fixation. The two FiberWire sutures were incorporated into the Endobuttons. The remaining 2 TiCron sutures were incorporated into the pectoralis major tendon stump.

The pectoralis major muscle that was reflected early in the procedure was reattached to the stump as well (Fig. 6).

The long head of the biceps tendon was not altered in this procedure. The incision was closed in a standard fashion. We utilized a combination of the techniques described above in this procedure in a fashion that we believe will give this patient the best opportunity for a positive functional recovery.

Outcome

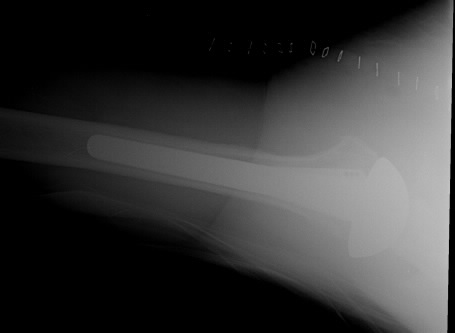

The patient was fitted in an abduction sling while still in the operating room. She experienced no complications post-operatively. Postoperative x-rays were obtained (Fig. 7). She stayed one night in the hospital for observation. The sling will be kept in a neutral position for six weeks with no range of motion in the left shoulder. After which she can begin some passive range of motion exercises. The patient was started on range of motion exercises for her elbow and wrist the day of surgery. We are anxiously awaiting her two and six week follow up visits to assess her progress.

References

- Gerhardt C Lehmann L Lichtenberg S Magosch P Habermeyer P. Modified L’Episcopo Tendon Transfers for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears: 5-year Followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009.

- Gerber C Vinh TS Hertel R Hess C. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff: a preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232:51–61.

- Boileau P Chuinard C Roussanne Y Neyton L Trojani C. Modified latissimus dorsi and teres major transfer through a single delto-pectoral approach for external rotation deficit of the shoulder: as an isolated procedure or with a reverse arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:671–682.

- Boileau P Chuinard C Roussanne Y Bicknell RT Nathalie Rochet N Trojani C. Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty Combined with a Modified Latissimus Dorsi and Teres Major Tendon Transfer for Shoulder Pseudoparalysis Associated with Dropping Arm. Clin Orthop Relat Res (2008) 466:584–593

- Moursy M Forstner R MD Koller H Resch H Tauber M. Latissimus Dorsi Tendon Transfer for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears: A Modified Technique to Improve Tendon Transfer Integrity. J Bone Joint Surg Volume 91(8) August 2009 pp 1924-1931.

- Iannotti JP Hennigan S Herzog R Kella S Kelley M Leggin B Williams GR. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Factors affecting outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:342-8.

- Aoki M Okamura K Fukushima S Takahashi T Ogino T. Transfer of latissimus dorsi for irreparable rotator-cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:n761-6.

Figure 1 Shows evidence of

superior migration of the humeral head.

Figure 2 Demonstrates a large defect

in the supraspinatus tendon.

Figure 3 Visualization of

superior portion of latissimus dorsi tendon

Figure 4 Osteotome at the insertion

of the latissimus dorsi/teres major tendons

Figure 5 Approximation of latissimus dorsi/teres

major tendon with pectoralis major tendon stump

Figure 6

Final fixation of pectoralis major tendon back to tendon stump

and incorporation of transferred latissimus dorsi/teres major tendons

Figure 7 Post-operative view reveals

improved glenoid/humeral head alignment

Propionibacterium acnes (P. Acnes) infection after total shoulder arthroplasty

Clinical presentation

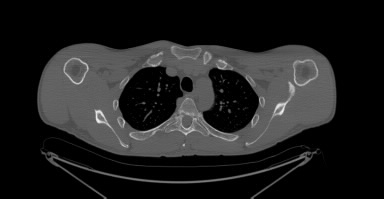

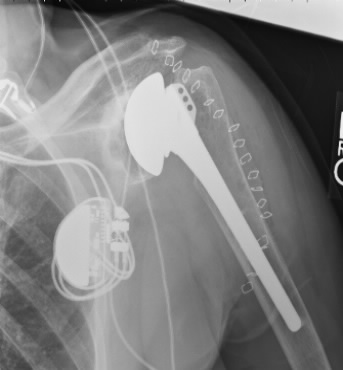

A 67 year-old male presented with severe pain stiffness and loss of function of the left shoulder after a total shoulder arthroplasty 5 years previously for advanced degenerative changes in the glenohumeral joint. He was initially comfortable after his TSA and did well for two years. Two years after his shoulder arthroplasty he had a left rotator cuff repair after which his shoulder remained stiff and painful with limited function. He presented to our service five years after his total shoulder arthroplasty. Plain radiographs suggested glenoid loosening with medial erosion and resorption of the medial portion of the humerus (Figure 1a). Bone scan showed increased uptake around the glenoid component. Pre-operative complete blood count sedimentation rate and C reactive protein values were all within normal range. Clinically there was no swelling or erythema around the shoulder. Our concerns included:

- Infection

- Loosening of components

- Poor glenoid bone stock

- Poor humeral bone stock

- Intra-operative fracture

- Access to glenoid if humeral component well fixed

- Axillary nerve injury due to multiply operated altered surgical field

Management

Due to the patient’s severe loss of shoulder function with persistent pain and stiffness we recommended revision surgery to include cultures before antibiotic administration removal of the glenoid component possible revision of the humeral component and debridement with lysis of adhesions.

At surgery the glenoid component was loose. There was a substantial amount of osteolysis of the proximal humerus and glenoid. The glenoid bone was eroded medially. There was no evidence of acute inflammation.

After removal of both the glenoid and humeral components the remaining glenoid bone was reamed to a conforming concavity after debridement of all fibrous tissue and cement. No prosthetic glenoid component was inserted. No bone graft was performed. A new humeral component was secured in proper position using impaction allograft with Vancomycin-impregnated allograft. (Figure 1b)

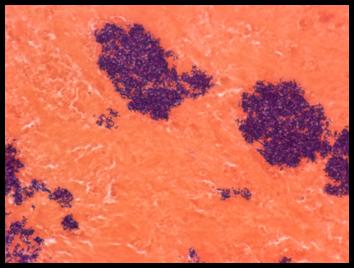

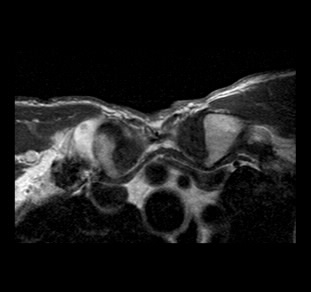

Multiple soft tissue and fluid specimens were sent for culture and microscopic examination. The pathology revealed clusters of gram-positive bacteria. (Figure 2). 5 out of 5 cultures became positive. Four specimens became positive at 5 days after surgery and one specimen 8 days after surgery. The patient was started on Ceftriaxone 2 gm IV q24 hours for six weeks via a PICC line followed by amoxicillin 1gm po tid for six weeks.

While the long-term outcome remains to be seen the patient is making excellent progress with his rehabilitation.

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

Figure 2

Revision Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty and P Acnes infection

Authors

Deana Mercer MD

Matthew Saltzman MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston J Warme MD

Frederick A Matsen III MD

Clinical Presentation:

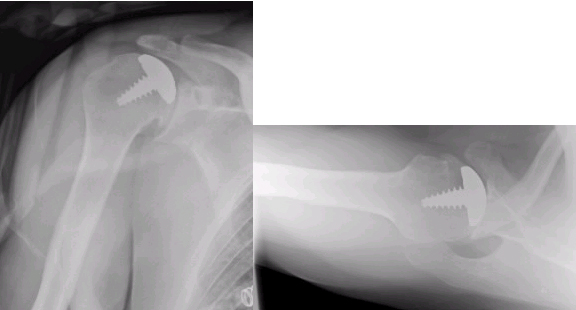

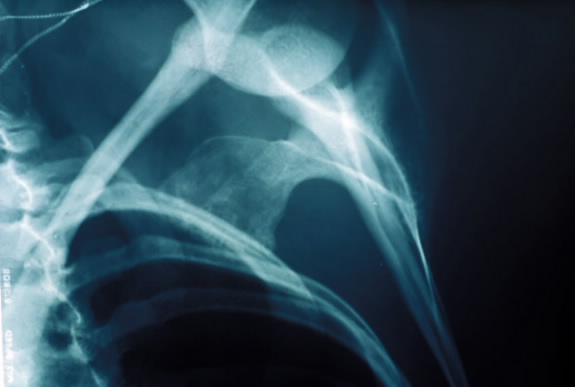

A healthy active patient in his 40's presented with severe right shoulder capsulorrhaphy arthropathy after a Putti-Platt procedure performed for recurrent shoulder instability. He presented with debilitating shoulder pain. Imaging studies showed posterior subluxation of the humeral head on the glenoid with flattening of both the humerus and the glenoid (Figure 1). Due to the severe posterior subluxation a posterior stabilizing procedure was considered. However intra-operatively it was noted that there was a significant amount of force required to maintain the humeral head in the correct anatomical position. There was complete destruction of the posterior glenoid squaring of the humeral head and subscapularis and anterior capsule contracture. It was decided that the best option was smoothing of the glenoid with humeral hemiarthroplasty.

Post-operatively he had improvement in comfort but had persistent posterior subluxation and not much improvement in function of the shoulder. One year later a second attempt at posterior stabilization was attempted without success. Due to severe posterior glenoid wear posterior capsular laxity with fixed posteriorly subluxated hemiarthroplasty and anterior capsule and subscapularis contracture the decision was made to proceed with a reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. (Figure 2)

He did well after his reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. His shoulder was stable. He had no shoulder pain. He regained function in his shoulder. He was able to golf swim surf and play tennis.

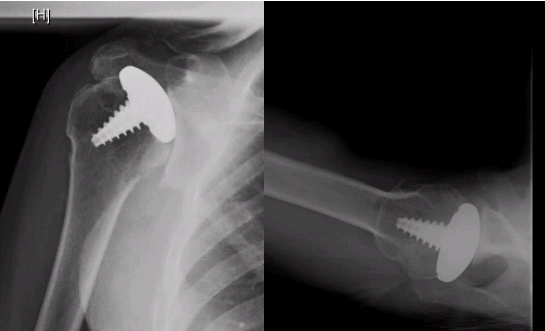

Three years later he noted pain in his shoulder after a golf swing. X-rays at that time showed increased lucency around the humeral stem and settling of the humeral component. The glenoid component had a significant area of lucency medial to the base plate and he had developed heterotopic bone extending from the humerus to the glenoid. (Figure 3)Our concerns included:

1. Infection versus severe osteolysis

2. Implant loosening

3. Difficult revision surgery with little glenoid and humeral bone stock

4. Impending humeral shaft fracture

5. Need for a long humeral stem due to severe bone loss in the humerus

6. Young active male

Management:

He returned to the operating room for a reverse total shoulder arthroplasty revision. Intra-operatively the humeral component was loose and easily removed with the cement attached to the component. There was a substantial amount of heterotopic bone extending to the area of the superior rotator cuff. There was no gross evidence of infection; however there was a thin membrane of tissue overlying the glenoid base plate with abundant granulomatous tissue. There was minimal wear of the polyethylene. The base plate was not loose but there was a 1 cm gap between the implant and the glenoid bone and no contact between the bone and base plate except for the central peg and screws.

Due to concern for infection staging of the surgery with implantation at a later date was discussed. It was decided to proceed with a single stage approach with immediate implantation of revision components due to concern for soft tissue contracture with loss of shoulder joint cavity as well as deconditioning and atrophy of the deltoid and scapula stabilizers.

After extensive debridement and irrigation of the shoulder joint the glenoid component was revised to a Delta II eccentric 42 glenosphere and metaglen. Secure fixation was obtained. A 10 cm long humeral component was cemented into position using vacomycin-impregnated cement. A 9 mm polyethylene component was used. The shoulder was reduced and was stable.

Multiple intra-operative tissue and fluid cultures were sent and several were positive for propionibacterium acnes. The infectious disease team was consulted. There was concern for contamination of the specimens. However because multiple specimens were positive it was decided to treat the patient with 6 weeks of ceftriaxone 2gm IV every 24 hours based on sensitivities.

Post-operatively the right shoulder was immobilized in a sling. Elbow and hand exercises were allowed. Range of motion exercises of the shoulder will be initiated at 6 weeks post-operatively.

Fig1

Fig2

Fig3

Fig4

Treatment of failed humeral head resurfacing

Authors

Deana Mercer MD

Matthew Saltzman MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston J. Warme MD

Frederick A. Matsen III MD

Clinical Presentation of Two Patients:

Case I:

A 31 year-old male presented to our clinic with complaints of severe shoulder pain. He initially injured his shoulder in 2002 while at work when his arm was pulled in the abducted externally rotated position. He did not dislocate his shoulder. He underwent a SLAP repair shortly after this injury. He re-injured his shoulder in 2003 when lifting a heavy object from a crouched position. He underwent a repeat SLAP repair shortly after this injury. He continued to have pain and underwent a diagnostic arthroscopy in 2004 which revealed cartilage damage. It was noted at this time that he had a loose suture anchor in the joint. This was removed. In April 2006 he underwent a humeral head resurfacing procedure. 1(Fig 1) He did not do well and developed stiffness for which he underwent an arthroscopic capsular release in December 2006. He had improved motion after this release but had persistent pain requiring narcotic pain medication for relief.

Case II:

A 55 year-old woman presented with complaints of shoulder pain. She had a history of recurrent right shoulder dislocations in her 30’s after a traumatic dislocation. This was treated with a subscapularis advancement procedure. She went on to develop capsulorrhaphy arthropathy with associated pain and stiffness. This was treated with arthroscopic debridement followed by humeral head resurfacing and fascial interposition graft. 2(Fig 2) After this procedure her pain worsened and was so severe she gradually lost use of her arm. Her main concern was worsening pain and stiffness of the shoulder.

Our concerns included:

- Infection

- Implant longevity in a young patient

- Altered surgical field and risk of neurovascular injury

- Patient outcome in revision shoulder arthroplasty

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fig 3

Fig 4

Management:

The first patient is a young laborer who developed glenohumeral degenerative changes secondary to a suture anchor which had dislodged was loose in the joint and through third body wear eroded his glenohumeral articular cartilage. He was treated with humeral head resurfacing which failed to provide relief of his pain. 3We recommended a revision to a total shoulder arthroplasty with a prosthetic glenoid. He did well after this surgery. His discomfort substantially decreased and he was able to wean from narcotic medications. (Fig 3)

The second patient is an active woman who developed capsulorrhaphy arthropathy following an instability procedure which was subsequently treated with humeral head resurfacing and interposition fascial graft. She had persistent pain stiffness and loss of function in her right dominant extremity. We recommended a ream-and-run procedure. 4 Intra-operatively the shoulder was very stiff and contracted. The subscapularis tendon was scarred and adhered to the biceps tendon. The arthrosurface implant was proud. The glenoid had eroded medially. 5 6Post-operatively she did well. At her 6 week follow up visit she had completely weaned off all narcotic medications and was taking Tylenol only intermittently. At her last clinic visit she was doing well she was back to her activities which included horse training and riding and was discharged from our clinic. (Fig 4 )

References:

- Copeland S. The continuing development of shoulder replacement: "reaching the surface". J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006 April 1;88(4):900-5.

- Bailie DS Llinas PJ Ellenbecker TS. Cementless humeral resurfacing arthroplasty in active patients less than fifty-five years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008 January 1;90(1):110-7.

- Franta AK FAU - Lenters Tim R. Lenters TR FAU - Mounce D Mounce D FAU - Neradilek B Neradilek B FAU - Matsen Frederick A.3rd Matsen FA 3rd. The complex characteristics of 282 unsatisfactory shoulder arthroplasties. - J Shoulder Elbow Surg.2007 Sep-Oct;16(5):555-62.Epub 2007 may 16.PMID- 17509900 OWN - NLM STAT- MEDLINE(1532-6500 (Electronic)).

- Lynch JR FAU - Franta Amy K. Franta AK FAU - Montgomery William H.Jr Montgomery WH Jr FAU - Lenters Tim R. Lenters TR FAU - Mounce D Mounce D FAU - Matsen Frederick A.3rd Matsen FA 3rd. Self-assessed outcome at two to four years after shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming. - J Bone Joint Surg Am.2007 Jun;89(6):1284-92.PMID- 17509905 OWN - NLM STAT- MEDLINE(0021-9355 (Print)).

- Matsen FA 3rd FAU - Bicknell Ryan T. Bicknell RT FAU - Lippitt Steven B. Lippitt SB. Shoulder arthroplasty: The socket perspective. - J Shoulder Elbow Surg.2007 Sep-Oct;16(5 Suppl):S241-7.Epub 2007 Apr 19. (1532-6500 (Electronic)).

- Matsen FA 3rd FAU - Clinton J Clinton J FAU - Lynch J Lynch J FAU - Bertelsen A Bertelsen A FAU - Richardson Michael L. Richardson ML. Glenoid component failure in total shoulder arthroplasty. - J Bone Joint Surg Am.2008 Apr;90(4):885-96.PMID- 18249566 OWN - NLM STAT- MEDLINE(1535-1386 (Electronic)).

Sternoclavicular Joint Infection

Authors

Amy Williams MS-4

Matthew Saltzman MD

Deana Mercer MD

Winston Warme MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Frederick Matsen MD

Clinical presentation

The patient is a previously healthy and physically active 41 year-old man who presented with a tender mass around his proximal right sternoclavicular joint for the last 5-6 months. He denied any recent trauma cat scratches or bites and use of IV medications or drugs. All PPD and HIV testing has been negative.

His symptoms and the size of the mass had waxed and waned over time. He also mentioned general fatigue over the last 5 months but denied any fevers or other associated symptoms. He has taken ibuprofen and a course of Cephalexin without any clinical improvement. He was recently placed on Amoxicillin by the Infectious Disease Service and has been taking it for three weeks. The patient still had not noted any improvement while on this treatment.

On physical exam there was boggy swelling around the right sternoclavicular (SC) joint without erythema or drainage. He had full and symmetric shoulder range of motion that was painful at the terminal range of forward elevation. He was neurovascularly intact distally.

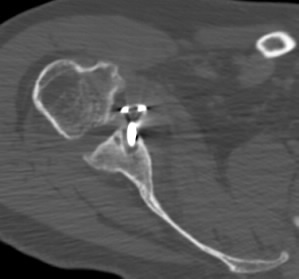

A plain radiograph of the clavicle showed asymmetry between the SC joints (Fig. 1) which was confirmed by CT (Fig. 2). An MRI showed a sternoclavicular effusion with no evidence of frank abscess (Fig. 3). A bone scan showed no abnormal uptake and all of the patient’s lab values were normal. A CT-guided aspirate of the SC joint and surrounding soft tissues revealed 2+ to 4+ Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) growth and pathologic evaluation was negative for malignancy.

Concerns

- Chronic Infection

- Potential for Loss of shoulder range of motion due to dissuse

- Potential need for Long-term antibiotics

- Potential for Contamination of aspirate

- Potential for Neurovascular injury if surgical debridement of the SC joint was undertaken

Management

Given the prolonged course of his condition we gave the patient the option of undergoing an open irrigation and debridement of the SC joint. The patient was agreeable to this plan. One week prior to the procedure the patient was taken off all antibiotics.

At the time of surgery a curvilinear incision was made over the clavicle. The capsule of the SC joint was incised to visualize the cartilage surfaces which appeared pristine. Minimal fluid was aspirated as the joint appeared benign and it was sent for gram stain and culture. There was some mild synovitis that was removed from the joint and sent for culture and pathology. The prominent anterosuperior aspect of the medial clavicle was resected smoothed and sent for culture as well. The joint was irrigated and the capsule subcutaneous tissues and skin were approximated. (Fig 4 5)

At follow-up he was doing well despite continued pain over the clavicle. The pathology showed no active or chronic inflammation and his cultures from the operating room now show 1+ P. Acnes growth.

He has full range of motion in his right shoulder and is neurovascularly intact distally.

He has been off antibiotics since before the procedure. Since there is no evidence of draining wound or of active infection we are going to keep him off of antibiotics. This is most likely an anterior chronic subluxation of the sternoclavicular joint rather than an infection. The 1+ growth of P. acnes could be a contaminant. We will continue to follow him clinically.

References:

- Ross JJ Shamsuddin H. Sternoclavicular septic arthritis: review of 180 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004 May;83(3):139-48.

- Crisostomo RA Laskowski ER Bond JR Agerter DC. Septic sternoclavicular joint: a case report. Arch.Phys.Med.Rehabil. 2008 May;89(5):884-6.

- McCarroll JR. Isolated staphylococcal infection of the sternoclavicular joint. Clin.Orthop.Relat Res. 1981 May;(156):149-50.

- Rockwood CA Jr. Odor JM. Spontaneous atraumatic anterior subluxation of the sternoclavicular joint. J.Bone Joint Surg.Am. 1989 Oct;71(9):1280-8.

- Higginbotham TO Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. J.Am.Acad.Orthop.Surg. 2005 Mar;13(2):138-45.

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fig 3

Fig 4

Fig 5

Anterior shoulder dislocation with glenoid bone loss treated with bone graft

Authors

Deana Mercer M.D.

Matthew Saltzman M.D.

Amy Williams MSIV

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston Warme M.D.

Frederick A. Matsen III M.D.

Clinical presentation

A 51 year-old woman presented to our clinic with complaints of left shoulder pain limited motion and instability. She injured her left shoulder in a fall in 2005. After the fall she had the sensation of her shoulder “dropping down” when she reached out in front of her. An MRI from an outside institution showed a Bankart lesion; no glenoid rim defect was mentioned. In March of 2006 the patient underwent a left Bankart and SLAP repair for recurrent anterior shoulder instability.

The patient continued to have persistent instability with dysfunction of the shoulder for which she underwent an arthroscopic rotator interval closure in October in 2006. Following this procedure she developed severe stiffness requiring manipulation under anesthesia in November 2006. After the manipulation her shoulder instability recurred.

The patient first presented to our clinic in July of 2007 complaining of recurrent anteroinferior instability and subluxation regardless of activity level. This was consistent with clinical examination findings. Plain radiographs at the time of her visit showed an anterior glenoid lip deficiency (Fig. 1). The glenoid deficiency was present on her initial radiographs following her fall in 2005. These findings were also seen on CT Scan (Fig. 2).

Concerns:

- Current Infection in this multiply-operated painful shoulder

- Poor anterior glenoid bone stock due to previous instability procedures with retained implants

- Potential for neurovascular injury due to altered surgical field.

- Graft site morbidity if instability procedure performed with autograft.

- Autograft morbidity if instability procedure performed with cadaver tissue

- Subscapularis failure in this multiply-operated shoulder

- Loss of shoulder motion

- Recurrent instability

- Potential for psychogenic re-dislocation despite shoulder surgeon's effort to stabilize shoulder

Management

Due to this patient’s recurrent instability and discomfort we recommended a revision instability repair using iliac crest bone autograft to reconstruct the anteroinferior glenoid rim defect.

At the time of surgery in February 2008 there was severe scarring present throughout the shoulder. The shoulder was grossly unstable and easily dislocated anteriorly.

The humeroscapular motion interface was released. The anterior neck of the glenoid was exposed and this area was freshened with an osteotome at the anteroinferior corner of the glenoid bone.

A left iliac crest graft was harvested. Its flat surface was then placed against the flat surface created at the anterior inferior corner of the glenoid and fixed there with three 3.5-mm cortical screws with washers (Fig. 3). Evaluation under anesthesia after anterior glenoid reconstruction revealed a stable shoulder.

Post-operatively the patient was placed on a physical therapy program that limited her to 90Ëš of forward elevation and 0Ëš of external rotation for three months. At her three month follow-up visit the patient was apprehensive and concerned about recurrent anteroinferior instability when the shoulder was relaxed at her side but on examination of forward elevation and abduction she was found to have great stability. The pain in her shoulder remained at a moderate level. Her plain radiographs at that time showed the humeral head well centered in the glenoid with no subluxation (Fig. 4). She continues to improve and has had no recurrent instability.

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fig 3

Fig 4

Complication of Latarjet Bristow for Recurrent Dislocation

Authors

Deana Mercer MD

Matthew Saltzman MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston Warme MD

Frederick A. Matsen III MD

Clinical presentation

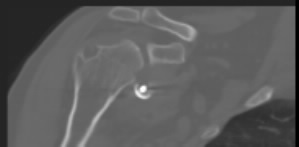

A 39 year old right hand dominant male who previously worked in construction presents with right shoulder pain and stiffness. He has a history of multiple right shoulder dislocations in his early 20’s treated with a Bristow procedure at age 21. (click shoulder instability for more information) He did fairly well and was able to work for 10 years. He has had no recurrent instability. He presents to our clinic with severe pain and dysfunction of his right shoulder. He takes over the counter analgesics which help minimally. He has been unable to work for the last 7 years due to severe pain in the shoulder. He has crepitus and pain with motion of the shoulder in any plane. He can forward elevate his shoulder actively to 45 degrees and passively to 90 degrees. He externally rotates to 10 degrees. He internally rotates to the sacrum. He has 4+/5 strength in internal/external rotation of the shoulder. He has difficulty with resisted forward elevation of the right shoulder due to pain. AP and axillary lateral x-ray of the right shoulder show a large Hill-Sach’s lesion of the proximal humerus. There is end stage degenerative disease of the glenohumeral joint. (click shoulder arthritis for more information) There is lucency about the screw and washer within the glenoid with abutment of screw against the humeral head with associated notching. The screw extends into the spinoglenoid notch raising concern for suprascapular nerve injury. (Fig 1) EMG/NCS was obtained and showed normal suprascapular nerve function. CT scan shows an irregular humeral articular surface and confirms notching of the humeral head against the screw with lucency about the screw and washer. (Fig 2)

Our concerns included:

- Potential for current infection

- Disability of the dominant extremity in a young laborer

- Potential for complications related to arthroplasty in a young laborer

- Unrealistic patient expectations in the face of severe muscle atrophy from prolonged disuse.

Management

As there is concern for infection CBC Sed Rate and CRP were ordered. These were all within the normal range. However we know that an indolent chronic shoulder joint infection cannot be ruled out on the basis of normal laboratory studies. This case presents a dilemma in that the patient is young and wishes to be active. The option of implant removal with shoulder joint debridment versus ream and run procedure

versus total shoulder arthroplasty was discussed with the patient. The next step in management will be removal of the glenoid screw and washer shoulder debridement and intra-operative deep cultures.

Click here for similar cases.

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fig 2

Post-surgical chondrolysis of the shoulder: a case-control study

Authors

Matthew Saltzman MD

Deana Mercer MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston Warme MD

Frederick A. Matsen III MD

Clinical presentation

A 37 year-old canine officer presented to the shoulder and elbow clinic complaining of disabling left shoulder pain. She had injured both shoulders during a fall at work two years prior to meeting us. Multiple procedures had been performed on each shoulder including: left subacromial decompression distal clavicle excision SLAP repair capsulorrhaphy debridement and right SLAP repair Bankart repair capsulorrhaphy and distal clavicle excision. Postoperative pain pumps were placed after both the left and right-sided surgeries however the right sided pump never functioned properly and continued to leak outside of her shoulder until the time it was removed. She had two subsequent arthroscopic lysis of adhesions performed on the left shoulder for residual stiffness following the original surgery. The articular cartilage on the left humeral head was noted to be nearly completely absent at the time of her last surgery. Multiple cortisone injections five viscosupplementation injections physical therapy and narcotics all failed to relieve her left shoulder pain. For the left shoulder she answered ‘no’ to all twelve questions of the Simple Shoulder Test.

On physical examination her right shoulder had 140 degrees of forward elevation 60 degrees of external rotation and internal rotation to T12. Her left shoulder was extremely stiff with only a 30-degree arc of rotation and flexion/extension. Radiographs showed significant left glenohumeral joint space narrowing (Figures 1 and 2).

Our concerns included:

- Suspected chondrolysis following arthroscopic surgery with use of radiofrequency ablation and post-operative pain pump

- The need for arthroplasty in a young active patient

- Our ability to get this patient back to a very active profession

Management

We discussed three options with the patient: (1) nonoperative treatment (2) hemiarthroplasty with nonprosthetic glenoid arthroplasty (‘Ream and Run’). (3) total shoulder arthroplasty. The patient is currently considering her options.

It is interesting to note that nearly identical procedures were performed on each shoulder and that chondrolysis only developed on the side that had a functioning postoperative pain catheter placed.

Click here for more information about shoulder arthritis.

Fig 1

Fig 2

Extensive heterotopic ossification after total shoulder arthroplasty

Authors

Deana Mercer MD

Matthew Saltzman MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston Warme MD

Frederick A. Matsen III MD

Clinical presentation

A 67 year-old male underwent a total shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral joint degenerative disease. His motion was started immediately after surgery and he was achieving 120 degrees of forward elevation in the days following the operation. It became progressively difficult to maintain this range of motion over the ensuing 2 months. A diagnosis of heterotopic ossification was made 2 ½ months after his original surgery (Figure 1). He presented to our shoulder and elbow clinic 9 months after his index operation and had only a toggle of rotation in both the flexion-extension and the internal-external rotation axis.

Our concerns included:

- Loss of function and mobility of the shoulder

- Inability to mobilize the shoulder secondary to a bone bridge uniting the glenoid and humerus

- Possibility of infection

- Involvement of neurovascular structures

- Component loosening

- Persistent stiffness after debridement

Management

Due to severe loss of function in the shoulder with progressive loss of mobility we recommended surgical excision of heterotopic ossification.

Intra-operatively the glenohumeral joint was found to be nearly completely arthrodesed with only minimal toggling of motion noted between the humerus and the scapula. There was extensive heterotopic bone extending from the inferior glenoid uniting with the humerus in two locations. Abundant scar tissue was lysed. The humeroscapular motion interface was freed.

The subascapularis was osteotomized at the lesser tuberosity. There was no normal subscapularis tendon but rather dense bone in the normal location of this structure. Even with this degree of release the shoulder was still frozen. The falciform edge of the pectoralis major was retracted to reveal additional heterotopic bone. With removal of this bone external rotation to 40 degrees was possible. Components were all well fixed without evidence of loosening. At this point intraoperative x-rays revealed removal of the majority of the heterotopic bone. It was elected to leave a small amount of bone extending inferior to the glenoid because of its intimate association with the axillary nerve (Figure 2).

Post-operatively the patient was placed on toredol and naprosyn and was treated with a single dose of 8 GY radiation on the day of surgery. He maintained 90 degrees of forward elevation 20 degrees of external rotation and returned to his usual activities including golf. The heterotopic bone did not reform. (Figure 3)

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fig 3

Failed total shoulder arthroplasty with loose glenoid prosthesis: revision without glenoid prosthesis reimplantation or bone graft.

Authors

Deana Mercer MD

Matthew Saltzman MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston Warme MD

Frederick A. Matsen III MD

Clinical presentation

A 61 year-old female presented to our clinic with a long-standing history of problems with her left shoulder. Her initial surgery was for instability. She later had a shoulder debridement for stiffness followed by a hemiarthroplasty. This became painful and was converted to a total shoulder arthroplasty. Her total shoulder arthroplasty was performed in the mid-1980s.

She never regained full function of her left shoulder but did have some improvement in pain until about two months prior to her visit to our clinic in July of 2008. At that time she noted a “tearing” sensation in her left shoulder and since then had unbearable pain. Her every day activities were greatly affected by this pain.

On physical examination it was noted that the patient had disuse atrophy of the deltoid supraspinatus and infraspinatus. She had about 80° of active forward elevation with painful range of motion.

Her radiographic findings were remarkable for a metal-back glenoid component dislodged from the glenoid and displaced into the inferior aspect of her shoulder joint. The humerus component appeared well fixed on x-ray. (Fig. 1).

Concerns:

- Neurovascular injury

- Intra-operative humerus fracture

- Component loosening

- Loss of range of motion

- Poor glenoid bone stock

- Infection

- Subscapularis failure

- Persistent pain

- Instability

Management

As the patient had a dislodged glenoid component we recommended removal of the glenoid component. We anticipated a glenoid defect. We recommended debridement of the glenoid without grafting or re-implantation.

At the time of surgery she had a large amount of gray/black tissue within the shoulder joint and surrounding the glenoid. There was a large cavitary defect in the glenoid. (Fig 2). The glenoid component was completely loose and was found in the soft tissues in the inferior aspect of the shoulder joint. It was removed without difficulty. There were multiple large pieces of bone cement in the joint which were removed. (Fig 3a)

Specimens were sent for culture and histological examination.

The glenoid was reamed using a "ream and run" reamer to provide a smooth concavity and the humeral head was replaced . The humeral stem was well fixed and left in place. (Fig 4)

Post-operatively the patient did well. Her pain was much improved when compared with her pre-operative pain level. Cultures were negative for any bacterial or fungal growth. Pathology showed fibroconnective tissue with degenerative changes granulation tissue and extensive foreign body giant cell reaction to foreign material but no signs of neutrophilic inflammation. Her post-operative course has been uneventful with marked improvement in comfort and shoulder range of motion. (Click here for more information about rehabilitation after shoulder arthroplasty)

Fig. 1 Pre-operative x-rays

Fig 1b

Fig 2

Fig 3a

Fig 3b

Fig 4

Avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis) of the humeral head of the shoulder after steroid use

Authors

Deana Mercer MD

Matthew Saltzman MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston Warme MD

Frederick A. Matsen III MD

Clinical Presentation

A 25 year-old female presented with severe right shoulder pain not well controlled despite being on several narcotic medications. She had received high dose prednisone 5 years prior to presentation for a severe asthma exacerbation which required hospitalization. A rheumatologic panel was obtained and she was positive for anticardiolipin antibody. All other rheumatological markers were negative and she did not have a rheumatologic diagnosis . She had no other risk factors for avascular necrosis such as alcoholism trauma or occupational exposure. On the Simple Shoulder Test she answered ‘no’ to all twelve questions.

On physical examination she had near full forward elevation external rotation and internal rotation but all were extremely painful. Crepitus was noted with shoulder motion. Radiographs revealed collapse of the humeral head with an associated crescent sign consistent with avascular necrosis (AVN) (Figure 1).

She in addition to humeral head AVN had right femoral head AVN with associated pain. She was wheelchair bound at the time of presentation due to severe right hip pain with ambulation. She was unable to use crutches or a walker due to severe pain in the shoulder. Her case was discussed with the hip reconstruction team. It was decided to proceed first with right shoulder hemiarthroplasty followed by hip hemiarthroplasty at a later date. This would allow her to better mobilize after right hip hemiarthroplasty with use of a walker.

Our concerns included:

- Osteonecrosis of the humeral head with significant collapse

- Longevity of arthroplasty in a young patient

- Possibility of glenoid involvement

Management

Examination under anesthesia confirmed nearly full passive range of motion. The shoulder was approached through the deltopectoral interval. Dislocation of the humeral head revealed severe destruction of the articular surface with significant collapse (Figure 2). Inspection of the glenoid revealed minimal scuffing of the anterior-inferior portion and largely preserved articular cartilage. Humeral hemiarthroplasty was performed using our standard technique (Figure 3).

We have used humeral hemiarthroplasty with impaction grafting to treat a number of cases of osteonecrosis of the humeral head. Recently a 23 year-old male returned 4 years after having undergone this procedure for AVN that occurred following a sustained course of oral steroids for a serious parasite infection (cystercosis). His initial radiographs revealed involvement of greater than 50% of the articular surface of the humeral head (Figure 4). At most recent follow-up he had minimal pain answered ‘no’ to all but questions 4 and 11 of the Simple Shoulder Test and had 160 degrees of active forward elevation and internal roation to T8. His most recent radiographs showed excellent position of the humeral prosthesis and no evidence of medial glenoid erosion (Figure 5).

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fig 3

Fig 4

Fig 5

Osteochondroma of the scapula causing a snapping scapula

Authors

Deana Mercer MD

Matthew Saltzman MD

Alexander Bertelsen PA-C

Winston Warme MD

Frederick A. Matsen III MD

Clinical presentation

A 22 year-old female presented to the shoulder and elbow clinic complaining of a dull achy sensation around her right shoulder for 12 months. She noted a grinding sensation under her shoulder blade with overhead elevation. Her past medical history and family history were noncontributory.

On physical examination prominence of the right scapula was noted with the Adams forward bend test (Figure 1). She had full active and passive forward elevation internal rotation and external rotation. Scapulothoracic crepitus was noted with forward elevation. Neurovascular examination was intact. Radiographs revealed a large pedunculated mass arising from the undersurface of the scapula (Figure 2).

Our concerns included:

- The painful quality of her symptoms

- Apparent growth of the lesion in a mature patient

- Potential for malignant conversion due to its inconspicuous location

Management

She was positioned prone on the operating room table and a curvilinear approach was made along the medial border of the scapula. After detachment of the rhomboids from the medial border of the scapula the mass was excised at the base of it’s stalk (Figure 3). The cartilage-capped specimen (Figures 3 and 4) was sent to pathology and the diagnosis of osteochondroma was confirmed.

For more information about common and rare shoulder conditions please visit UW Medicine Center Shoulder and Elbow Clinical Services.

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fig 3

Fig 4

Medial scapular winging treated with pectoralis transfer

Clinical presentation

A 24-year old female presented to the Shoulder and Elbow Clinic with a 6-year history of dominant shoulder pain fatigue and difficulty working as a hairdresser. Her symptoms began following the birth of her eldest child during which she was pulling vigorously against her spouse with the affected extremity. Her physical exam was significant for profound medial scapular winging with attempted forward elevation with and without resistance (Video 1). Nonoperative treatment including scapular stabilization exercises failed to improve the function of her extremity. Radiographs and MRI were normal. EMG/NCV were normal.

Our concerns included:

- Her need to abduct and elevate her extremity to function as a hairdresser

- Possible resultant chest asymmetry from a muscle transfer procedure

- Excursion of the pectoralis tendon to the inferior border of the scapula

- Possible need for allograft tissue to augment the pectoralis tendon

Management

With the patient in the sloppy lateral position a low-anterior axillary incision was made in line with the anterior axillary fold. The deltopectoral interval was defined and the sternal head of the pectoralis major was taken off the humerus while taking care to protect the clavicular head as well as the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. Once the excursion of the tendon was deemed adequate to reach the inferior border of the scapula a posterior tibial tendon allograft was sewn to the posterior aspect of the pectoralis tendon using a running locking suture technique. The tendon/graft complex was tunneled posteriorly and secured through drill holes in the inferior border of the scapula as it was held in an anatomically reduced position.

The patient wore an Alignmed S3 brace for the first six weeks that supported the scapula. She demonstrated active forward elevation of 170 degrees with complete resolution of scapular winging six weeks following surgery (Video 2). The low anterior axillary incision was barely visible and her axillary contour was nearly symmetric with the contralateral side (Figures 1 2). She returned to work as a hairdresser at postoperative week 12.

Fig 1

Fig 2

Complication of Latarjet Bristow for Recurrent Dislocation

Clinical presentation

A 45 year-old right hand dominant male presented to our shoulder and elbow clinic with progressive right shoulder pain. He had undergone a Bristow procedure 20 years earlier for shoulder instability. He described a sharp aching pain and crepitation with any movement of his shoulder. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories two intraarticular corticosteroid injections and glucosamine had failed to provide any significant relief.

On physical examination he had 90 degrees of forward elevation 0 degrees of external rotation and internal rotation to L5. Rotator cuff strength was excellent and neurovascular examination was intact. Radiographs revealed advanced degenerative changes of the glenohumeral joint and a seemingly intraarticular location of the screw used for the previous instability procedure (Fig 1 2).

Our concerns included:

- Intraarticular hardware position causing destruction of the joint surface

- Potential for neurovascular injury during revision surgery because of altered anatomy

- Potential for recurrent instability

- Potential for glenoid component loosening if total shoulder arthroplasty was attempted in this young active patient

Management

Examination under anesthesia revealed 3+ anterior instability with accompanying crepitus. After careful exposure through the previous deltopectoral approach the screw was found to be penetrating the joint with resultant destruction of the humeral articular surface (Fig. 3). The screw was easily removed and the coracoid was found to be nonunited to the anterior glenoid. A humeral hemiarthroplasty with nonprosthetic glenoid arthroplasty (“Ream and Run”) was performed (Fig 4).

Click here for more information.

With a resurgence of interest in bony procedures such as the Bristow Latarjet and iliac crest bone block for managing cases of instability with substantial glenoid defects it is imperative to recognize each of these cases carries the risk of hardware problems (Zuckerman and Matsen JBJS 1984).

References:

Zuckerman JD Matsen FA 3rd. Complications about the glenohumeral joint related to the use of screws and staples. JBJS-A. 1984 Feb; 66 (2): 175-80.

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fig 3

Fig 4

Fig 5

Unconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for rheumat

Clinical Presentation

This is the radiograph of a 60 year old woman with chronic rheumatoid arthritis who presented to us with problems 4 weeks after left total elbow arthroplasty. She had a similar procedure performed on the opposite side without problem. One week after this surgery she felt a "clunk" in her elbow and then had difficulty moving it without discomfort. Radiographs showed the elbow had dislocated (see figure 1). A closed reduction was performed but 2 weeks later the dislocation recurred. Open reduction and a soft tissue reconstruction was performed at that time. Now the elbow is again dislocated swollen and painful on all motion--she keeps it in a splint at all times. Her lateral elbow incision is relatively calm but the sutures are still in place. She has had two surgeries and one manipulation in less than one month. Her exam indicates ulnar nerve irritation but she is otherwise neurovascularly intact.

Our concerns included:

- the patient's loss of elbow function

- wound status

- neurovascular status

- risks of revision of cemented prosthesis in soft rheumatoid bone

- incisional approaches

Management

Closed reduction was attempted under anesthesia and fluoroscopy. This could not be accomplished.

Open reduction was attempted after ulnar nerve dissection through a new posteriormedial approach. A stable reduction could not be achieved. Revision to constrained total elbow was accomplished with minor penetrations of ulna and humerus in process of cement removal. Post operative range was 0-135 degrees. Neurovascular status intact. See post operative radiograph (figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

ORIF of proximal humerus fracture nonunion

Clinical presentation

This is the radiograph of the right shoulder of a 50 year old woman who presented with a chronic atrophic non-union of her humerus (see figure 1). She sustained the subtuberous fracture in a fall 6 months ago. She was treated with closed reduction and sling immobilization. At 6 weeks mobilization was started however over the ensuing months she had progressively increasing pain in her arm.

At her consultation visit with us examination revealed pain and crepitance on movement of the arm. There was no evidence of sepsis or neurovascular impairment. Her general health was excellent.

Our concerns included:

- The loss of bone around the fracture site.

- The local osteopenia.

- The method of internal fixation (if a prosthesis was not used).

- The challenge of obtaining union between the tuberosities and humeral shaft if a prosthesis was used.

Management

In our view the primary problem here was not the articular surface nor the length of the bone but rather the challenge of getting the tuberosities to heal to the shaft. We elected a method of treatment which respected the compromised bone quality and which maximized the contact between bone of the proximal and distal fragments. On these bases neither interpositional bone graft metallic internal fixation nor a prosthesis was used. The shoulder was approached through a deltopectoral incision to protect the deltoid muscle. The distal aspect of the proximal fragment was carefully carved to receive and interlock with the proximal end of the distal fragment. The insertion of the peg of the humeral shaft in to the hole in the head was secured with six large (#5) non nonabsorbable sutures passed through holes in the proximal shaft and then through the proximal humeral metaphysis out the cuff insertion and around the tuberosities. Iliac crest autograft was added around the non-union site. The fixation was robust so early gentle active motion was started immediately.

Radiographs taken 6 months later show a united fracture (see figure 2). The arm is one inch short and the deltoid lag is resolved. The patient is now pain free has good use of the shoulder and is pleased.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Anterior-inferior glenoid reconstruction for recur

Clinical presentation

This is the radiograph of a 25 year old male with a history of recurrent anterior dislocations of his right shoulder (see figure 1). His original dislocation occurred 5 years ago following a seizure. Unfortunately over the ensuing two years his seizures were poorly controlled resulting in further dislocations. Over the last three years he has had two surgical procedures (a Bankart repair and a revision Bankart repair with soft tissue augmentation) but continues to have instability whenever his arm is brought into abduction and minimal external rotation. Due to the dislocations he is unable to work or perform normal daily activities above shoulder level. His epilepsy is well controlled on medication.

On examination the patient was very apprehensive with his arm in abduction and in thirty degrees of external rotation. With his arm by the side he could externally rotate to sixty degrees without discomfort in comparison to eighty degrees on the other side.He had a functioning rotator cuff and subscapularis. He had no evidence of ligamentous laxity a negative sulcus sign and a negative jerk test.

Our concerns include:

- Significant deficiency of the anterior / inferior glenoid.

- Early degenerative change of the glenohumeral joint.

- The history of seizures.

- The failure of two previous repairs.

Management

Despite early degenerative changes on X-ray the patient's primary functional problem was instability. Examination under anesthesia revealed that there was no effective anterior glenoid lip on the load and shift test. Surgical findings confirmed the lack of an anterior inferior glenoid lip a large recurrent Bankart lesion a large Hill-Sachs defect and early degenerative changes. The subscapularis was intact.

We concluded that a robust reconstruction of the anterior glenoid was essential to stabilizing this shoulder and that the patient's history demonstrated that this could not be accomplished with soft tissue procedures. Thus we reconstructed the anterior glenoid using a contoured iliac crest graft with capsule interposed between the graft and the humeral head.

One year following surgery the bone graft remains stable (see figure 2) and the patient uses the shoulder for daily activities without apprehension instability or complaints of pain.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Revision shoulder hemiarthroplasty for infection

Clinical presentation

This is the radiograph of a fifty year old woman with rheumatoid arthritis who presented to our unit with a complex shoulder history (see figure 1). Six years previously she underwent a right total shoulder replacement and did well until four years later when she fractured her humerus below the stem of the prosthesis in an automobile accident. The fracture was treated with open reduction and internal fixation of the humerus using a plate and screws. Postoperatively however the arm became infected with staph aureus requiring removal of the internal fixation and prosthesis and the insertion of antibiotic-impregnated cement beads around and within the humeral shaft. At the time of presentation to us the patient's chief complaint was pain and inability to use her arm due to weakness and instability. She answered "no" to all 12 questions of the Simple Shoulder Test. There was no clinical evidence of infection a sedimentation rate of 25 and the shaft fracture appeared healed. Her main question was whether a new joint could be re-inserted.

Our concerns include:

- Had the humeral shaft fracture united?

- Was there still residual infection?

- Was it possible to revise this to a hemiarthroplasty?

- Could a humeral stem be inserted all the way down the humeral shaft?

Management

After thorough discussion of the risks with the patient she decided to have us explore the shoulder with the possibility of inserting a prosthesis if there was no evidence of sepsis. Without preoperative antibiotics the shoulder was exposed through the previous deltopectoral incision. A large amount of residual scar tissue was identified yet there was no macro or microscopic evidence of underlying sepsis. After cultures were obtained intravenous antibiotics were administered. The shaft appeared to be solidly healed. Although our initial plan was to insert a long stemmed component; removal of the beads from the intact shaft proved impossible. Rather than splitting the humerus to remove the remaining beads we cut down the stem of a prosthesis to fit the available space in the medullary canal. A solid press fit was achieved without additional cement. This prosthesis provided a smooth and stable articulation with the remaining glenoid.

Forty-eight hours after surgery the patient was discharged with a comfortable shoulder which she could elevate to 140 degrees and externally rotate to forty degrees. She was pleased and already more functional than at the time of admission.

Figure 1

Shoulder arthrodesis for spondylo-epiphyseal dyspl

Clinical presentation

This is the radiograph of a 70 year old woman with spondylo-epiphyseal dysplasia who has had severe limitation of her right shoulder motion since birth. Over the last few years she has progressively experienced severe pain which prevents her from using this arm and from sleeping. She also uses a wheel chair for ambulation because of dysplastic involvement of her spine hips and knees. Her left shoulder remains relatively unaffected.

On examination her right shoulder is relatively fixed in internal rotation. Any use or motion of the joint is painful for her and produces crepitance. Her attitude is very positive.

Our concerns include :

- Marked disuse osteopenia.

- The technical difficulty of a shoulder arthroplasty.

- The potential for improved function after an arthroplasty due to the chronicity of her condition.

- The feasibility and potential benefit of an arthrodesis.

Management

The patient clearly identified pain at rest and on use of her shoulder as her primary problem; she had thoroughly adapted to the loss of motion. Because of her serviceable left arm and her need for a strong right shoulder for transfers and wheel chair ambulation we recommended a shoulder arthrodesis using internal fixation for immediate return to function.

At surgery the virtual absence of glenohumeral motion was verified. The shoulder was fused in the same position it had assumed for 70 years: slight flexion and abduction with 45 degrees of internal rotation. The arthrodesis was secured with a pelvic reconstruction plate. She began using her arm on the first post operative day. Three months after surgery the shoulder was essentially painless and allowed function in the necessary activities of daily living.

Figure 1

Chronic anterior shoulder dislocation

Clinical presentation

This is the radiograph of a 45 year old man who presented to our clinic with a painful left shoulder of 5 months duration (see figure 1). His chronic anterior dislocation apparently resulted from a fall after an epileptic seizure. An unsuccessful attempt had been made 1 month earlier to reduce the dislocation in the emergency room. His current complaint was disabling pain and limited range of motion.

On examination the patient held his right shoulder in fixed internal rotation. Obvious asymmetry was present around the shoulder girdle when compared to the contralateral side. His humeral head could be palpated anteriorly and inferiorly and any form of shoulder movement caused severe pain. His axillary nerve was functioning and his remaining neurovascular examination was normal. The patient had a history of alcoholism and epilepsy poorly controlled by medication.

Our concerns include :

- The patients' general health and well-being.

- The possibility of maintaining a reduction following an open procedure.

- The condition and viability of his humeral head.

- If a hemiarthroplasty was necessary what soft tissues would maintain stability in this patient.

- Would there be a need for a bony procedure around the glenoid to establish stability?

Management

Despite the patient's history of alcoholism and poorly controlled epilepsy we thought it appropriate to try to treat the patient and his shoulder due to his chronic disabling pain.

No attempt was made to perform a closed reduction due to the chronicity of the dislocation.

A routine deltopectoral incision was made exposing the subscapularis and dislocated humeral head. Care was then taken to identify and protect the axillary nerve. It was impossible to openly reduce the humeral head due to a large Hill Sachs lesion involving at least 50% of the articular surface and severe contracture of the posterior structures.

Due to the humeral head destruction yet an intact glenoid a decision was made to perform a hemiarthroplasty rather than a TSA. An extensive release of the posterior capsule and cuff was performed before inserting the humeral component. This was then reduced with difficulty and showed signs of anterior subluxation when the arm was rotated away from neutral. The component was therefore placed in some 45 degrees of retroversion and a more extensive posterior release was performed around the glenoid. We did not feel the necessity to place an anterior bone block on the glenoid although this would be a possibility if instability persisted.

Due to concerns of patient compliance and the potential for instability post-operatively he was placed in a shoulder immobilizer for 6 weeks.

The current radiographs are shown demonstrating a located humeral head and a small amount of heterotopic ossification which commonly occurs following a chronic dislocation (see figure 2). No further episodes of instability have occurred at 6 months follow-up and the patient is currently satisfied with the result.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Proximal humerus fracture

Clinical presentation

This is the radiograph of a 50 year old otherwise normal woman who presented with a comminuted fracture of her proximal humerus sustained in a fall (see figure 1). She had a normal neurovascular examination.

Our concerns include :

- Could this fracture be successfully managed non-operatively?

- If operative intervention were necessary what would be the best method of internal fixation?

Management

The fracture was managed nonoperatively. At 6 weeks the radiographs (see figure 2) showed early callous and the position remained acceptable so gentle motion was commenced. Twelve months later the fracture was solidly united. She had full use of her arm and a full range of movement both of her shoulder and elbow.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Limb salvage hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus parosteal osteosarcoma

Clinical presentation

This 45 year old female presented with a one-year history of gradually increasing left shoulder pain and gradual loss of range of motion (see figure 1). The patient recalled an injury about one year prior to presentation when some boxes she was carrying were forced into her shoulder by a closing door.

On examination no soft tissue mass was present around her shoulder region.There was tenderness to palpation over her anterior deltoid. There was loss of motion of the affected shoulder particularly involving external rotation and forward elevation. Her neurovascular examination was unremarkable.

Her general health and overall physical examination was normal expect for a past history of benign thyroid nodules.

Our concerns include :

- Establishing an accurate diagnosis of the bony / soft tissue lesion.

- What further investigations were necessary?

- Possible management strategies depending on the diagnosis.

Management

Our differential diagnosis from history and radiographic appearance included myositis ossificans high grade surface osteosarcoma and parosteal osteosarcoma. Further studies used to help differentiate and stage the lesion included a CT scan of her shoulder and chest MRI of her shoulder technetium bone scan and appropriate blood workup.

Following these studies an open biopsy was performed through the anterior edge of the deltoid which could be later sacrificed if a formal resection was required. Biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of "parosteal osteosarcoma".

The options of management were then discussed at length with the patient and included:

- Limb salvage via a proximal humeral allograft

- Shoulder disarticulation

- Tikhof-Lindberg

- Allograft arthrodesis

- Mega-prosthesis

A mutual decision was made to perform a limb salvage procedure via a proximal humeral allograft and a cemented long stem Neer prosthesis as seen in the current radiograph (see figure 2). This was performed through an extended anterior deltopectoral approach. Adequate margins were achieved by resecting the proximal 1/3 of the humerus including part of the cuff and part of deltoid pectoralis major latissimus dorsi and teres major. Neurovascular structures were able to be preserved.

The remaing cuff and capsule were reattached to the allograft. The deltoid insertion to the humerus was preserved. Microscopic pathology revealed adequate margins.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Charcot arthropathy

Clinical presentation

A 43 year old right-hand-dominant male with a history of a nonspecific injury to his left shoulder while skiing 15 years ago presented to the University of Washington Shoulder and Elbow Service complaining of crepitus in his left shoulder. Approximately 3 to 4 weeks prior to presentation the patient noted acute onset of painless and progressive left shoulder swelling. The patient's past medical and surgical histories were otherwise unremarkable.

Physical examination was remarkable for a 10 x 15 cm nontender mass in the anterolateral aspect of his left shoulder. Neurovascular examination was remarkable only for a vague nondermatomal decrease in pinprick sensation in his left upper extremity. Proprioception and vibration sensation were preserved.

Plain radiographs of the left shoulder revealed destruction of the humeral head with an associated soft tissue mass (see figure 1).

Laboratory tests were unremarkable.

Management

The differential diagnosis included Charcot joint septic arthritis and neoplasm. The patient was taken to the operating room for open biopsy of his left shoulder mass. Cultures were negative. Histological examination showed chronic inflammation reactive new bone formation and fibrosis suggestive of neuropathic arthropathy. Subsequently the patient had an MRI of the cervical spine which demonstrated a cervicothoracic syrinx (see figure 2).

The patient was evaluated by the Neurosurgery Service and underwent a syringoperitoneal shunt.

Since arthroplasty and arthrodesis in this group of patients have a historically high failure rate no further surgical intervention in planned. The patient has been educated as to the disease process as well as conservative treatment to maximize his function.

Figure 1 - Destruction of the humeral head

with an associated soft tissue mass

Figure 2 - Cervicothoracic syrinx